The subject of my race produces confusion. Understandably too, for my physical features and given name connote opposite meanings. My name, Rajin Patel, screams of an Indian heritage, whereas, my dark brown skin and thick curly hair point to my Kenyan heritage.

Typically, people guess I am Sri Lankan, Trinidadian, Somalian, Eritrean, Ethiopian, Jamaican, Fijian, Guyanese, or Sudanese.

When they exhaust the list, I reveal: I am half-Kenyan, half-Indian. Afterwards I get asked: which of my parents is black and which is brown? I say, neither, because both of my parents are half-Kenyan and half-Indian, and of course, this creates more confusion.

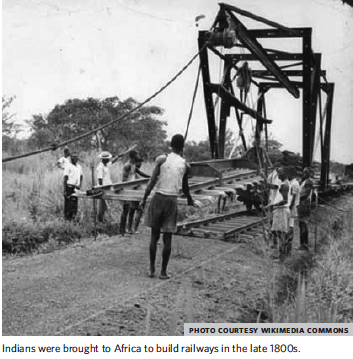

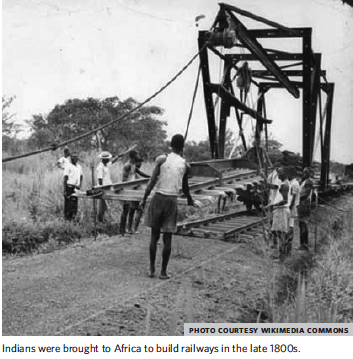

I explain that in the late 1800s, the British used indentured Indian workers to build the Kenyan-Ugandan railways. Eventually, those Indians mingled with Kenyan women and produced multiracial people like myself. Those multiracial people, known colloquially as Jotawa in Swahili, mingled with each other.

After the history lesson, people scratch their heads. They then reply, “Well, doesn’t that only make you a quarter black?”

Realizing I have gone over people’s heads, I use the purple analogy. I ask them, “When you mix blue and red, what do you get?”

They reply, “Purple.”

Then I reply, “Ok, so when you mix purple with more purple, you do not get magenta or indigo, you get purple!”

Growing up, I always felt like an outsider. In my home, notions of religion, race, custom, food, and dress were indefinite and illusory.

Worst of all, I lived in a predominantly South Asian and West Indian populated suburb. I witnessed the zeal and excitement of colourful cultural celebrations. As well, community schools fostered expression of cultural identity. Despite all of this, I felt empty.

For most of elementary and middle school, I tried being “brown.” I cut my curls off and tried to speak Punjabi. I had mostly Sikh friends, who often called me “kala,” Punjabi for black.

By high school, my blackness was the punchline to every joke. I wanted to provoke verbal and fist fights. Eventually, I got tired of getting mad, and just accepted it. I feared rejection.

In 10th grade I briefly had a “black” phase. However, my “black” personality resembled a poorly impersonated stereotype. I sucked at basketball and looked ridiculous with baggy pants. I hated rap music too. I tried to speak in “ebonics” and Patois, but only embarrassed myself.

By the end of high school, I detested my “blackness” and “browness.” I associated both colours with rejection. So, I decided to be neutral, i.e. white.

I scoffed at non-English languages, and judged people of colour, sporting their countries’ flags. I shopped at West 49, used words like “dude,” and listened to rock music. I wanted to be white. It seemed easier.

For a long time, I told myself I would not date anyone “ethnic.” I thought I would never be accepted by an “ethnic” family, being a half-breed and all. I touted and hollered my bullshit, rationalizing it as innovation.

Little did I know I would fall in love with an Indian girl, worse a Brahmin, the top of the Indian caste system.

Within a year, I felt more comfortable with myself. I embraced my race, and tried to think critically about racial discourses.

Currently, there is an epidemic in black multiracial identity. Like myself, I see “mixed” people favouring 50 per cent of their genes, while hiding the other 50 per cent.

In my family, I have witnessed my half-white cousins completely disowning or being willfully ignorant over their black half. They assume white identities. My Indian-looking cousins exaggerate their fondness for Indian culture, while denying their Kenyan heritage.

This is not exclusive to my family. I have known many multiracial people of all combinations. I have noticed a pattern of favouring one race, over the other (particularly the least-black half of their genes).

This monochromatic view of race permeates the media. For example, Obama, a half Kenyan like myself, is honoured as the “first black president”; however, we often forget: Obama’s mother is white. If Obama were dubbed the 44th elected white President of the United States, a media frenzy would ensue.

Other “black” celebrities with white mothers, like Alicia Keys, Halle Berry, and Drake face the same racial reduction. This notion is a modern day continuation of the one-drop rule, an outdated view of race, which justified the enslavement of “mulatto” slaves, stating one per cent of blackness amounts to 100 per cent.

For a long time, I believed in this view of race. I struggled to chose one of my identities. Currently, I have learned to love both sides of myself. Like the colour purple, I exist as the combination of two colours, yet I am my own colour.

I always used the purple analogy to explain my race to mock people’s ignorance; however, I always failed to see that within the analogy, lurked a positive truth not only for myself, but e

Gooseberry by Raquel Abdool, Contributor2009 Acrylic on illustration board

This piece was created after a trip to Guyana, where I’d often see kids picking gooseberries off the trees to pickle and eat.

Rajin Patel

Contributor