Brendan Rowe

Staff Writer

Are video games art? This question has been asked by developers and players for almost as long as videogames have been made.

One of the most critical articles on the subject comes from the March 6, 2000 issue of Newsweek, and entertainment writer Jack Kroll. On the heels of the release of the Play- station 2, Kroll says right out that “Games can be fun and rewarding in many ways, but they can’t transmit the emotional complexity that is the root of art.”

The letters column of the March 27 issue, however, proved just how contentious that statement was. The editor noted there were over 100 responses, and published three anti- Kroll letters, as well as a few Kroll supporters, including one who said, “Kroll deserves a Pulitzer for his brilliant insight in exposing techno-art for what it really is. The day that a game becomes successor to Picasso or Shakespeare is the day that culture dies and we follow the path of the Romans into decay. Thank goodness for the likes of such critics, without whom our youth might soon sink into a cultureless void.”

Film critic Roger Ebert, however, is probably the most famous anti-“games-as-art” debater. Ebert’s argument boils down to player interactivity and the human experience.

He argues “Video games by their nature require player choices, which is the opposite of the strategy of serious film and literature, which requires authorial control.”

Jim Emerson, the editor of Ebert’s website, offered some further insight into his boss’ opinion. “Ebert began by explaining why he felt a game (particularly the shoot-shoot, point-scoring kind) was not an experience equivalent to that of reading a great novel like, say, The Great Gatsby because games don’t delve very deeply into what it means to be human.”

The problem with any discussion of this sort is that the definition of art is inherently personal. As the cliché goes, beauty is in the eye of the beholder. Furthermore, every debate on the topic seems to classify all games together, as one category of art, but that’s not really how it works.

Emerson, who has his own views on the nature of video games, uses this example. “It’s the same as asking ‘Are movies art?’ or ‘Are books art?’ Of course, it depends on the individual movie or book. Are we talking The Benchwarmers or 2001: A Space Odyssey? The Bridges of Madison County or Emma? Pac Man [sic] or Shadow of the Colossus?”

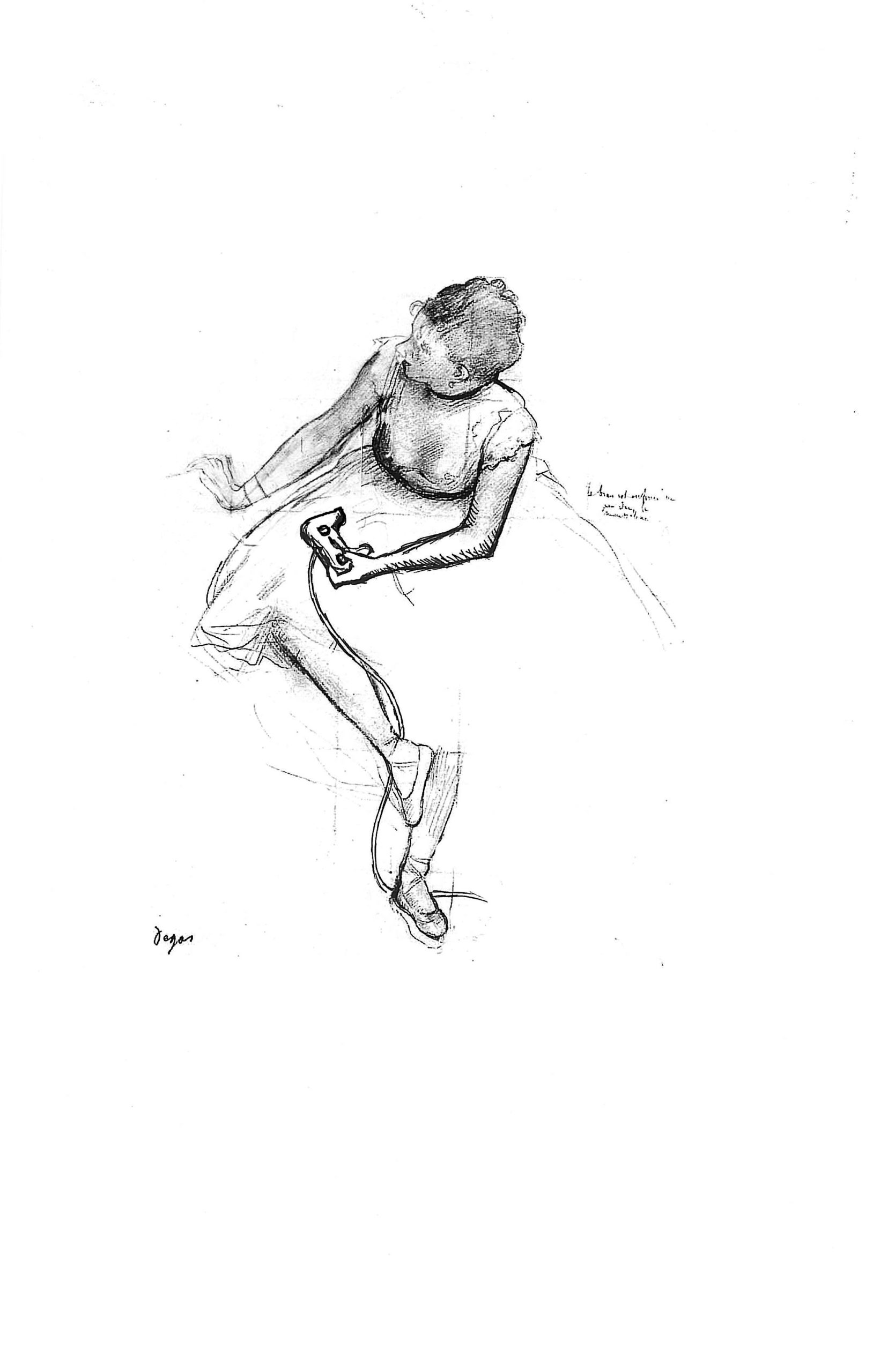

Kellee Santiago, president of independent game studio thatgamecompany, took a different approach in her 2010 TEDxUSC talk “Stop the Debate!” She compares today’s video games to cave paintings – sure they’re not high art like the Mona Lisa or Beethoven’s ninth, but someday they might be.

Her example is extremely apt because videogames are still a young medium. Films took a while to become art; literature took a while to become art; music took a while to become art. But video games are still making progress.

When IGN interviewed Ted Price, founder of Insomniac Games, Inc., in 2009, he said “I think what’s cool about games today is that they have become so much more diverse than they were 10 years ago, and we do have games that are leading the way in terms of promoting games as an art form. But we also have games that really are all about pure fun. I mean, they’re not trying to tell the next great story and they’re not trying to set the world on fire with their graphics, but they’re pure fun.”

Today’s video games industry is one of sequels and formulas. This model of the game industry seems to mimic that the of movie industry, where the big studios are turning out big blockbusters and the smaller independent studios are producing lower budget creative works. These lower budget games are free from the formulaic thought and instant commercial success that drives the bigger companies. These creative people are behind new classifications like the art games genre that has begun to seep into video game conversations.

Examples of art video games include Tale of Tales’ 2009 release The Path; Molleindustria’s Every Day the Same Dream (2009); 2008’s Passage by Jason Rohrer; Limbo, from Playdead Studios; and Pixalante’s ImmorTall. These games are new ways of looking at the world and experiences. They ask questions about the human experience, something Ebert said games could never do.

Then again, Ebert went on to clarify his point, saying games can indeed be art, but that they would never reach the artistry of Shakespeare. Wait, what? Hey, Ebert, are you saying that after 2,000 years video games won’t have reached some sort of reasonable artistic level? Because if you crunch the numbers, Shakespeare was nowhere near the beginnings of his art form.

So here we are in 2010, a long ways away from Kroll’s article in the year 2000 and even longer still from the beginnings of the industry in the late ’70s. The debate still isn’t settled. Maybe it won’t ever be settled. The thing to keep in mind is it’s still early for video games. Who knows where the sands of time will lead us next?

Maybe we should stop wasting time debating the artistic merits of games and actually make some artistic games. Maybe if we spent less time debating whether it’s art or not and made something artistic, we’d all be better off.

Answering that new age-old question