Bernice Afriyie | Arts Editor

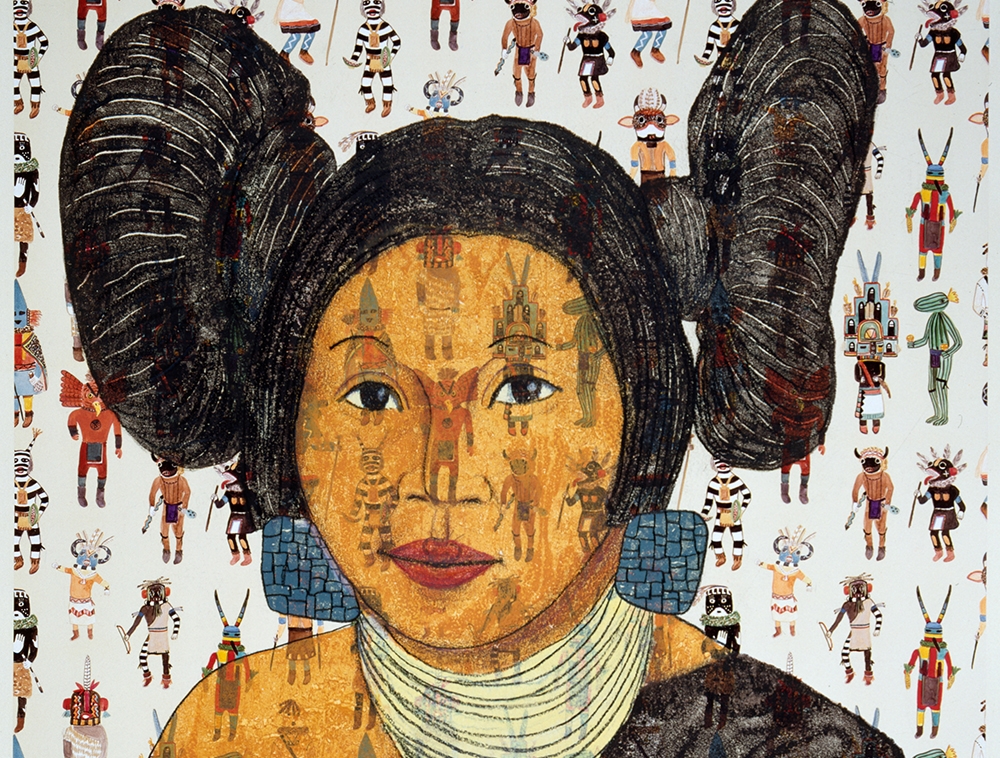

Featured image: The Indigenous Friends app creates a home away from home for Indigenous students to connect with one another. | Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Nowadays, there’s an app for anything and everything. Are you lonely or cold and need someone to cuddle with? Do you, for some reason, want to track all the places you’ve used a washroom? Do you find pleasure in popping pimples but have run out of ones of your to own to pop or willing pop-ees? Not surprisingly, there are apps to satisfy all these weird urges and pleasures.

Alejandro Mayoral-Banos, an Indigenous scholar doing his PhD in communication and culture, is using apps to make meaningful connections. When Mayoral-Banos first arrived in Canada from Mexico, he faced discrimination and exclusion. After meeting other Indigenous students at York and hearing their stories of otherness, Mayoral-Banos realized that the struggle of finding and maintaining community, and creating culture and art was something they all shared.

Mayoral-Banos developed an Indigenous app for York and University of Manitoba students to combat this problem. “The Indigenous Friends app is an application seeking to generate safe spaces for Indigenous youth,” he says.

“It aims to provide access to traditional counseling, generate social networking and provide information about resources and events around Indigenous lives. It allows young Indigenous students and community members to build networks for sharing information and supporting other peers in their life journey.”

Crucial to the formal structure and design of Mayoral-Banos’ app is a deep understanding of Indigenous culture and the art of building homes and communities.

“This application was developed through the incorporation of the Indigenous knowledge of tipis within a software development methodology. In the same way you raise a tipi is how you develop an Indigenous mobile application,” he says.

While creating the app, Mayoral-Banos depended on the input and participation of community elders, faculty, staff, alumni and traditional knowledge keepers.

“When a person crosses the door of a tipi, that human being is accepting the protocols of the tipi’s owners in the regard to the behaviours, beliefs and values that must be followed inside such shelter. Therefore, to access this tipi/mobile application, you must follow the protocols within Indigenous Friends.”

The Indigenous Friends app compensates for the lack of physical space and representation for Indigenous people at York and across Canada with a technological space for Indigenous people to connect. Much of Indigenous culture and art centres around community and kin relationships, making it difficult for artists to create when they feel isolated or disconnected from their communities.

Aspiring to bring together various Indigenous people across Canada, the app has the ability to overcome issues of abandonment and loneliness that many teens face. The app can also function as an online gallery; artists can share their creations in a space that aesthetically takes into account their perspectives in its construction.

Art galleries that display Aboriginal art provide a home for Indigenous artists, allowing them to have a voice and educate the masses on Indigenous history and culture.

However, these galleries and exhibits often feature works that are transported away from their place of inception or displayed in areas where they are predominantly viewed by non-Indigenous people.

In such contexts where art becomes a spectacle for others as opposed to an expression of faith or tradition among Indigenous people, we risk preserving the artifacts of a culture without the meaning associated with the objects.

“We have created different [measures] to keep this space safe and free of discrimination and harassment,” adds Mayoral-Banos.

One of these measures is how users sign up for the app. In order for York students to register, users must identify as an Indigenous person and hold a free of charge membership tag from the Centre for Aboriginal Students Services.

The app provides its users with access to traditional counseling through crisis buttons screens that allow them to communicate with elders or traditional counselors.

For Indigenous students who may feel isolated and as though they have no one close by to reach out to, the app features a directory of Indigenous people who are around them. There are chats and public forums for like-minded individuals to share information and engage in conversations.

Mayoral-Banos anticipates that the app will influence hundreds of Aboriginal students in different disciplines who are struggling with their identities. It will provide a space for people to connect and also shape how Indigenous software and hardware methodologies are shaped in the future.

“The largest challenge of developing the Indigenous Friends app was reconciling Indigenous knowledge with technology because the latter has been used several times to colonize Indigenous cultures,” says Mayoral-Banos.

He reports that it was hard to translate the role of animal clans into the general conceptualization of roles in apps. Standardized methods of developing roles in apps are based on administrators and users, whereas Mayoral-Banos’ app infuses Indigenous understandings of roles into the functionality of the application.

“These roles are trying to balance the levels of power inside mobile application,” says Mayoral-Banos. “There is not a ‘superuser’ role, which can do all the actions within the app. The responsibilities and duties are distributed among the users.”

By attacking the form of applications, the Indigenous Friends app ensures that it’s not reproducing problematic structures of oppression. It’s technologically savvy while also showing that it’s possible for communities to exist without blatant power hierarchies.

The app is up and running but is still in its testing phase. People who identify as Indigenous can download the app at the Apple Store and Google Play Store for free.