Kanchi Uttamchandani | Contributor

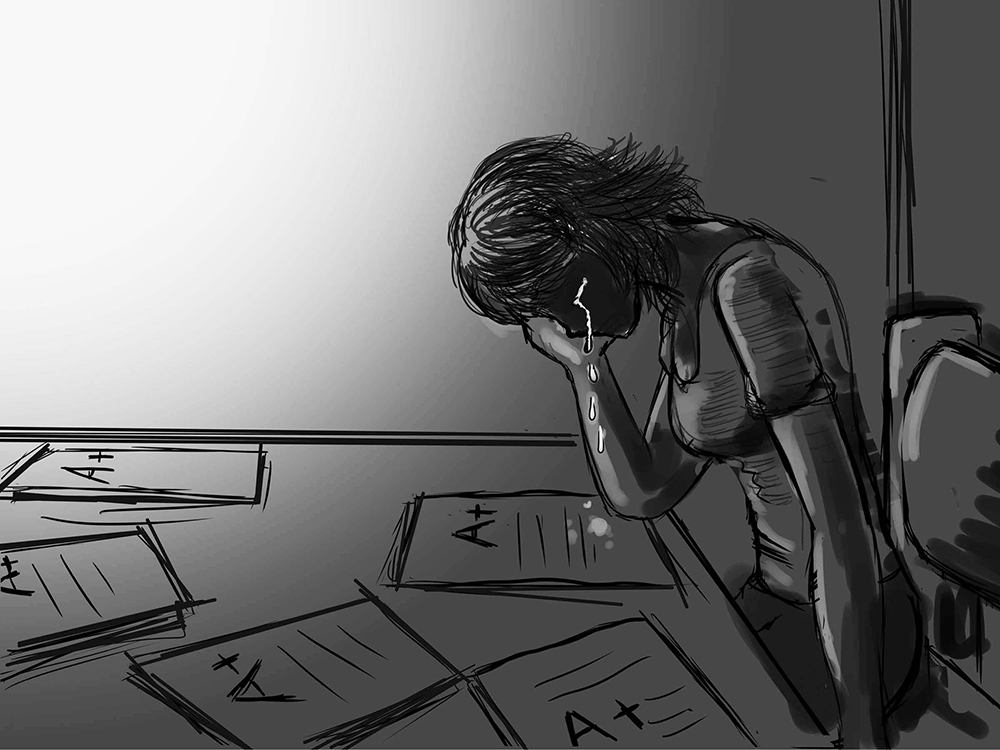

Featured image: Findings indicate that Asian-Canadian students are more likely to exhibit symptoms of perfectionism and are at a higher risk of suicide. | Cedric Wong

Suicide among students may have another contributing factor: their culture.

Gordon Flett, York psychology professor and Canada Research Chair in personality and health, has conducted research on links between perfectionism and suicide and how this apparent phenomenon is internalized in different cultures.

Flett says that his research is motivated in part by the fact that there are too many perfectionists who become suicidal, as well as growing evidence of mental health problems among students.

While the research was conducted at the University of British Columbia in collaboration with Professor Paul Hewitt, Flett asserts that, historically, the same issues and findings are found in research conducted jointly at York and UBC.

The findings indicate that Asian-Canadian university students are more likely to exhibit symptoms of socially prescribed perfectionism and perceived pressures from family, work-related and intimate relationships.

They also scored significantly higher on thoughts of suicide, suicidal risk and depressive symptoms, compared to their European counterparts.

Flett notes that several researchers have suggested that Asian societies have a greater emphasis on achieving perfection.

“This is amplified by cultural views that emphasize the close ties between the student and his [or] her family, so that failure to achieve is a source of shame for the entire family. This, of course, amplifies the pressure,” he further explains.

Shubha Kaushik, second-year communication studies student, stresses that the idea of duty and responsibility within the family drives the concept of perfectionism.

“Being a Southeast Asian myself, I know the familial and societal pressures of trying to be ‘perfect’ in every aspect. I believe the idea of familial duty and the sense of responsibility is very strongly imposed in Asian culture, which brings about the stress to be considered perfect,” she says.

Flett states that the implications of this research call for preventive interventions that will boost the resilience of not only vulnerable students, but all students, given the pressures inherent in university life.

“This became increasingly apparent to me during the years I spent as undergraduate director in Psychology. Every week, I would meet with York students who needed advice and support in dealing with stressors,” he says.

“It is important that students get the message that much of what they are experiencing is normal and common to other students and not a reflection of personal deficiencies or defects.”

Flett suggests the essential incorporation of a proactive approach that seeks to improve not only emotional resilience, but also resilience in the face of academic setbacks and interpersonal difficulties.

“A significant issue for university students that is sometimes exacerbated by cultural factors is the unwillingness to seek help and pretend that everything is fine, if not perfect, while hiding great distress,” he states.