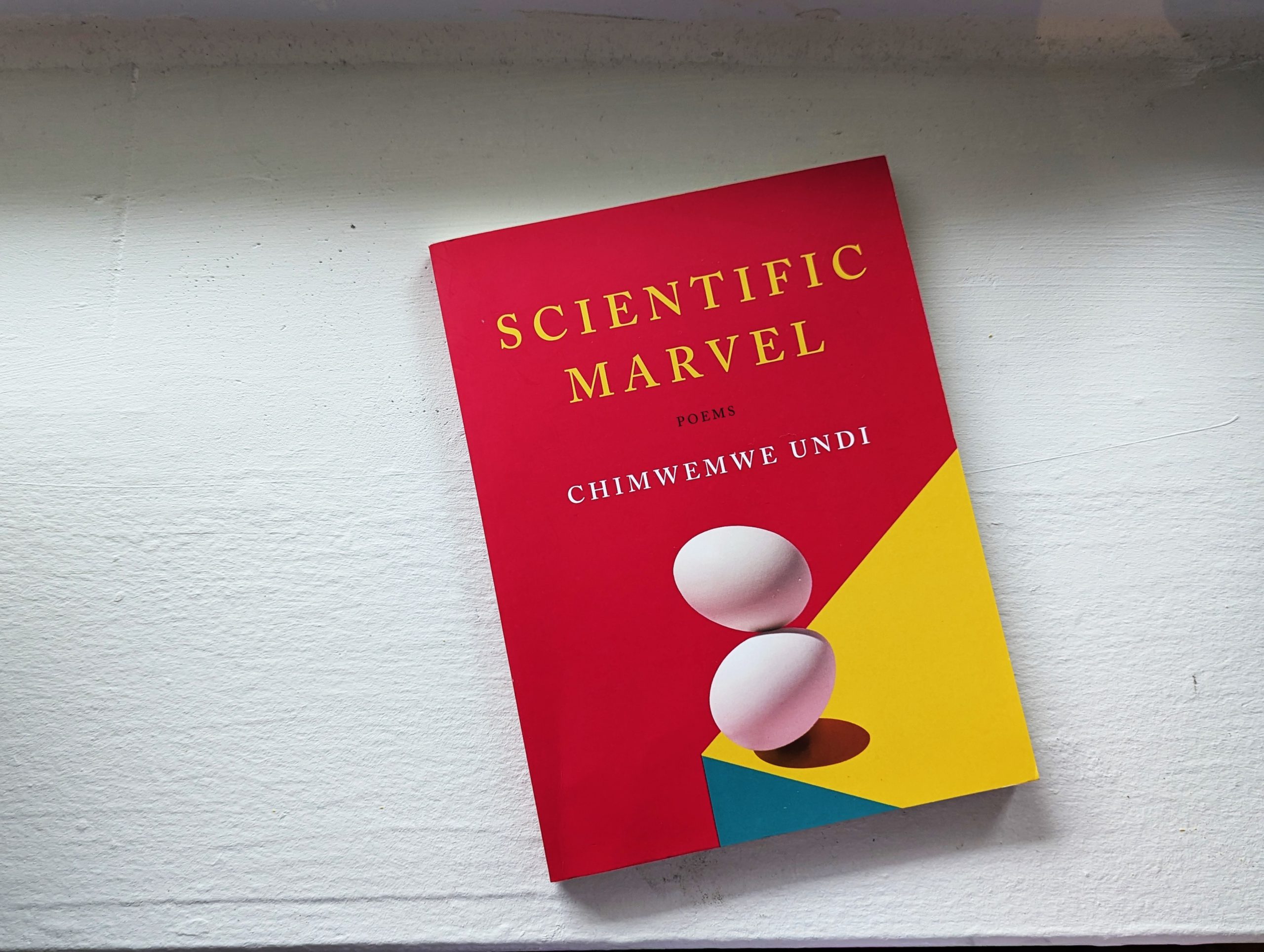

The world’s greatest bards may be the feminist wallflowers frequenting your weekend ragers. At least, that character description is not far afield of the poetic persona of Scientific Marvel, the debut poetry collection of York alumna Chimwemwe Undi.

Sunny and frank, heartfelt and cheeky, Undi’s style digs beneath the mantle of pedestrian life to produce gems of insight on race, identity, motherhood, illness, love, death, despair, humour, and cynicism with a measured hopefulness in marvelous, glistening achievements of verse. Her deft hand earned Scientific Marvel the Governor General’s Literary Award in Poetry earlier this year.

The second poem in the collection, “Winnipeg Poem,” is a sheepish but loving shrug over a portion of Scientific Marvel’s contents: poems about Winnipeg. It may be that very few readers can be tempted to care about a daydreamer’s portrait of the small-city, wide-open prairie flora and fauna, and yawning blue sky regionalism that writing about Winnipeg almost always mandates. Those who might already be invested will quickly recognize the tropes of prairie poetry: “4. Lamenting (winter-specific)” and “13. Invoking Guy Maddin’s My Winnipeg.” Undi does not try to attach frills to her poetry to draw in the prejudicially disinterested. She brings her ardent love of her subjects and her unrelenting playfulness together in kernels that are fundamentally relatable even to non-prairie lifers.

Undi favours the couplet; each stanza in poems like “Grunthal, Manitoba (2019)” spill into each other in alternating superindentations winding around the page much like the Red River carves itself into Manitoba’s landscape. But she never lets this preference for form grow stale through the collection; she is constantly pulling other levers in her laboratory. Poems like “Comprehensive Ranking System” stand out because they can be read in several ways: as two individual poems running parallel to each other, or one whole poem rent in two.

While some critics (including myself) have been entranced by Undi’s duo of epithalamiums — poems about marriage — “Auto-Epithalamium” and “Epithalamium Ending in Death,” the unsung showstopper is “Assemblage.” Not only does it exhibit even more of Undi’s range, this time in ekphrasis — writing about a work of art — “Assemblage” animates Winnipeg-based Ekene Emeka-Maduka’s already kinetic painting “Morning Assembly” into a scene of Black resistance. “Our dozens Black alive,” the poetic personae challenge the reader, “watching, watching back.”

Undi’s background in law spurs her return to blackout poems made from legal documents. Undi’s ability to excavate meaning from the deeper strata of case law and other legal literature continued to surprise me from top to bottom. “No, Suffer Here,” was an especially potent reaction, effectively oxidizing a Canadian law derived from Mavis Baker’s fight for permanent residence in Canada, to a commentary on the false promises nascent in Canada’s siren call to people around the world.

What really elevates Scientific Marvel to new heights are Undi’s borderline-ethnographic idioms. Poems like “Girls Who” read like a watchful introvert’s diary entries. The persona recalls watching “girls doubled up in the stall, smoke tickling over the peeling door,” as well as being charmed and accepted by “girls who pull the denim up around your flesh” and “who envy the big and small of you.” These glimpses into micro-social worlds feel like catching up with an old friend, collecting the nuggets of their universe shared with you in confidence.

Through it all, Undi’s disarming brand of humour shines, too. One poem dedicated to one of Canada’s oldest queer clubs and Winnipeg landmark, Club 200, is aptly titled “Ode to 200 from Each of my Tits.” It is almost self-explanatory, discarding the glamour, refinement, and reverence we might associate with an ode to anything in favour of something more generously real, like boob sweat.

Grounded as the collection might seem, the stakes are often stratospherically high for Undi’s poetic personae. In “Search History,” we see the emotional burden that underlies loving humanity on a granular level so deeply, as the poem begins with search queries like “how will [I know the lyrics]” and spirals into dread over the end of the persona’s known world: “how much longer [will the sun last].” Despite these deep-rooted, almost nihilistic anxieties, each poem marks a commitment to live on and love on anyway.

Teeming with gale-force observational power while still economizing language, the poems in Scientific Marvel conjure high-definition images from life on-the-ground. Undi manages to tenderly hold out, palm open, a bottled guide with a stolid and clear-eyed gaze.