Kate Hudson

Production Manager

Final exams may drive you to the edge of sanity, but compared to what Norio Ota, director of Japanese studies at York University, went through at his Japanese high school, our academic lives are a cakewalk.

“When I was going through the entrance examinations, it was called ‘the exam from hell,’” said Ota. “I had to work until two to three in the morning every single day because I had to study for ten or twelve subjects at the same time, and then get up 6:30a.m. and go to school.”

He could tell I was shocked. Ota shook his head with a dismissive smile, “I wasn’t exceptional. Many people had to study the same way. We had a saying: If you sleep for four hours, you will fail the entrance exam. You have to sleep only for three. Seriously.”

It’s difficult for me to imagine an educational culture so different from my own.

“Well, many people went through this in Japan at those times. We thought about dying, and all those things, because the pressure was just enormous.”

“It was okay for me because I thought of it as one hurdle I had to overcome.”

Decades later, Ota still works until 2 or 3 am many days of the week, teaches overtime, trains high school teachers across Canada via videoconferencing, and recently helped coordinate a new Japanese language program at Havana University.

His peaceful smile, balanced demeanour and humility gave me the impression of self-awareness, dedication, and a man truly in love with his work.

“I feel appreciated by other people – I think that’s a source of work ethic for me,” said Ota. “It’s not just culturally ingrained. I love what

I do.”

A certain school of Western psychologists, however, might use a different word to describe his behaviour.

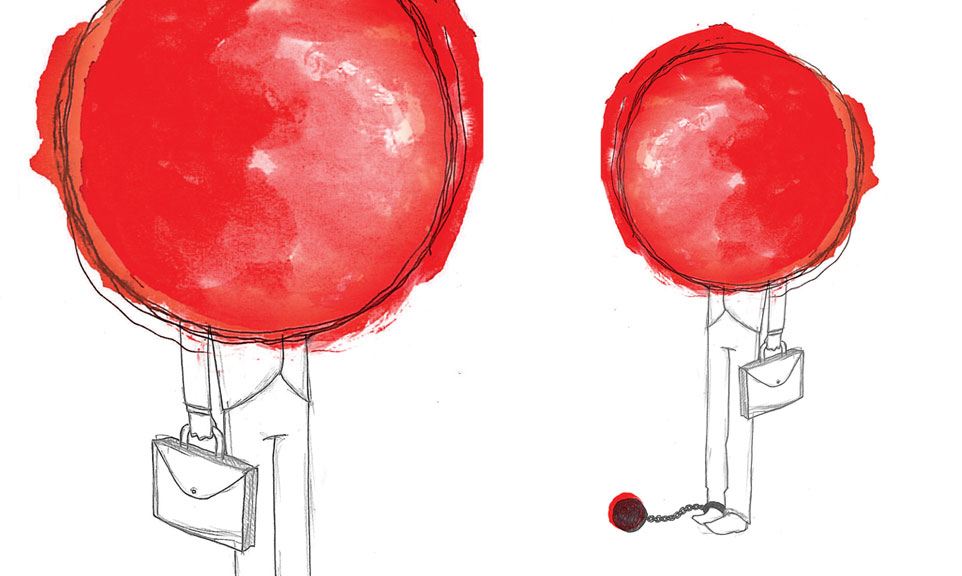

Workaholism.

Work·a·ho·lic (n. circa 1968)

The term workaholic has been used informally to refer to white-collar and public service workers who ‘work too hard’ since it was coined in 1968 by American psychologist Wayne Oates.

However, there has been much academic discussion about what the term actually means in a clinical context, and considerable difficulty reaching a consensus.

Some early studies in workaholism looked at workers’ attitudes toward their jobs, while others focused on their behaviour, i.e. the number of hours worked per year. For example, Mosier (1983) defined a workaholic as someone who works more than 50 hours a week regardless of his psychological condition; Cherrington (1980) defined a workaholic as having an “irrational commitment to excessive work”; Machlowitz (1980) focused on the workaholic’s positive enjoyment of work.

Later studies attempted to place workaholics on a spectrum of “work involvement, a feeling of being driven to work, and work enjoyment”, differentiating between workaholics who enjoy their work and those who resent it.

The ‘Japanese Work Ethic’

The Japanese have a reputation for outworking their Western counterparts. But do the numbers support anecdotal evidence like professor Ota’s high school entrance exam experience? Is Japan a nation of workaholics?

At Japan’s economic peak, the numbers indicated a resounding yes. In 1980, Japanese worked an average of 2121 hours a year while Canadians and Americans both worked just over 1800. To put that in perspective, if you took two weeks of vacation, you would have to work about 8.5 hours every day – not including breaks – to meet the Japanese average.

While cultural collectivist attitudes are sometimes cited, Ota explained there is a clear economic explanation for this phenomenon.

“For a long time, until the beginning of the bubble economy, many [Japanese] worked for the same company until they retired. That was the source of loyalty in the company. These people worked really hard because they identified with the company.”

Overworking was such a serious issue that a word, kar?shi, was coined in the late ’80s to describe death or suicide attributed to work-related stress. Kar?shi prompted the Japanese government to begin research initiatives and enact legislation to force workers to take holidays.

Today, the problem is less severe, but over 10,000 continue to die from kar?shi every year – almost as many causalities as the March 11 earthquake crisis this year.

White collar workers and high level executives are among the most vulnerable. Even pre-university students, who are exposed to high levels of stress, are affected by kar?shi; Japanese students have one of the highest suicide rates for their age group in the world.

Bursting the Bubble

Westerners continue to view Japan as a workaholic society, but the trend may be changing.

In 2009, Japanese workers laboured an average of 1714 hours a week – only 15 more than Canadians – and actually less than American workers, who worked 1768.

This statistic forces us to rethink typical stereotypes about cultural pre-dispositions and look at economic factors in defining trends in

overworking.

“After the economic bubble burst, what happened was that Japanese companies started laying off and firing people, so the so-called life-time employment system has collapsed since then.” said Ota. “Many people felt the same way I did: ‘Why should I spend my whole life working for a big corporation?’ A different value orientation was introduced. Not all at once, but gradually.”

While Japanese workaholism may be subsiding, for Canadians, there are no signs the problem is going away. Since workaholics tend to be high-functioning members of society, their problems often go unnoticed.

Bryan Robinson, PhD., author of the best-selling Chained to the Desk, thinks the subject is, at least in some ways, taboo.

“Cultural attitudes towards workaholism have changed very little,” said Robinson. “In a downturn economy, where people are desperate for jobs, they don’t want to talk about working too much. Plus, with the advent of wireless technology, electronic devices are invading personal time more than ever before.”

A lot of the problem is awareness.

“People still don’t get how damaging work addiction is. It continues to be praised and misunderstood, especially in a time when many people don’t have jobs.”

According to Robinson, university environments are particularly at risk, and desperately need to take action.

“Universities are notorious for enabling work addiction with huge expectations and very few boundaries […] Universities and any workplace at risk for burnout should be encouraging self-care among faculty, not expect multi-tasking, which only activates the stress response, and they should hold seminars on the dangers of overworking and the damage done to marriages and children.”

Robinson found it hard to think of a North American campus he could hold up as a positive example. “I don’t know of any who are doing it right,” he said.

A Positive Outlook

In a very personal moment, I described my own struggle with workaholism to professor Ota. I spend up to 15 or more hours a day working at Excalibur as a designer, a writer and a manager, an ethic that differs little from the way I’ve approached my work since middle school.

Despite all of this negativity, not everyone views intense commitment to work as a bad thing. The key to staying healthy and balanced for an intense worker, he said, is passion and

humility.

“I used to think I worked for self-satisfaction; it was only after an important person in my life died that I realised, actually, my life is not for myself. When you can feel your life is not for yourself, all negative feelings like anger, jealousy, everything disappears. Once you reach that stage, you keep your peace of mind.”

I told him maybe this was true, but my drive to work sometimes took over the rest of my life.

“You are part Japanese, remember,” he laughs, referring to my one-quarter Japanese background. “It’s in your blood!”

Compiled by Chloe Silver and Kate Hudson with files from oecd.com

Addicted to Work