There is a scene in Quentin Tarantino’s latest film, The Hateful Eight where a person gets raped. The movie does not gloss over this scene. It is drawn out to an uncomfortable length as every painful detail of the character’s rape, torture, and subsequent murder is half shown, and half narrated to the audience. The only thing that stops the scene from being unbearably cruel is the fact that the victim is a person who makes his money hunting down black people. For some, it might be satisfying to see a racist murderer get his comeuppance, but for the audience I watched it with, and myself, it was not. It made my skin crawl and my stomach churn.

The common, answerless question about life on Earth is, “Why do bad things happen to good people?” Throughout most of Tarantino’s filmography runs the related question of “should bad things happen to bad people?” Despite his reputation as someone who fetishizes violence, Tarantino always makes sure to show its negative consequences in deceptively subtle ways.

Consider 1977’s Star Wars, where the good guys are in danger of having their base destroyed by the bad guy’s giant battle station known as the Death Star. Their response is not to evacuate the base, or to deactivate the Death Star’s weapons system, but rather to send people to blow it up and everybody onboard. And so, Luke Skywalker, Han Solo, and Chewbacca explode the giant machine, kill hundreds of thousands of enemy soldiers, receive medals for their work, and every child watching the movie learns that mass murder is a happy thing.

Whether or not the destruction of the Death Star is ethical is up to debate, seeing as how it had previously been used to disintegrate an inhabited planet, but I think most would agree that the unflinching glee with which our heroes commit the act is disturbing to say the least. So how did director George Lucas and his team know that people would not react to the scene with the slightest discomfort? Simple cinematic techniques, such as making the bad guys wear masks so audiences feel less compassion for people whose faces they cannot see, and by making sure the faces that are seen are old and ugly, in contrast to our young, attractive protagonists.

Tarantino does not use these empathy-dampening tricks. In Django Unchained, there is a scene where the protagonists snipe a wanted killer and is punctuated with the killer’s son running up to his fallen father like Simba in The Lion King. In Kill Bill, there is a scene where the heroine maims and massacres a bunch of gangsters trying to kill her and ends with a reminder that many of them are teenagers, in over their heads. In Inglourious Basterds, Tarantino juxtaposes the slaughter that Brad Pitt’s heroic character inflicts on Hitler’s soldiers with Hitler’s own propaganda that celebrates the slaughter of Americans. Thus, Tarantino compares himself to Joseph Goebbels and his audience to the Nazis, sitting in a movie theatre and cheering on violence against other human beings.

And of course, in The Hateful Eight, he makes sure that the audience gets to see every flutter of emotion and pain in the villains’ faces before they meet their demise, and this difference is the only thing that makes his characters “anti-heroes” and Lucas’ characters “heroes.” The Hateful Eight is for adults while Star Wars is for children because The Hateful Eight is honest.

At one point in the film’s near three-hour runtime, Tim Roth’s character explains the difference between justice and revenge, or “frontier justice” as he calls it. He explains that the difference between a murderer getting hanged after being found guilty in a court of law and the family members of a victim dragging the murderer into the snow and hanging them. The latter feels good and the former does not. Justice delivered for the sake of emotional satisfaction “is always in danger of not being justice.” People delight in the climax of Star Wars and, therefore, it is not justice.

Nowadays, it seems like every day we read about some new and fresh atrocity committed by people against people. Do not let this make us forget the importance of compassion and that just because something feels good does not mean it is the right thing to do.

Jimmy Zhao, Staff Writer

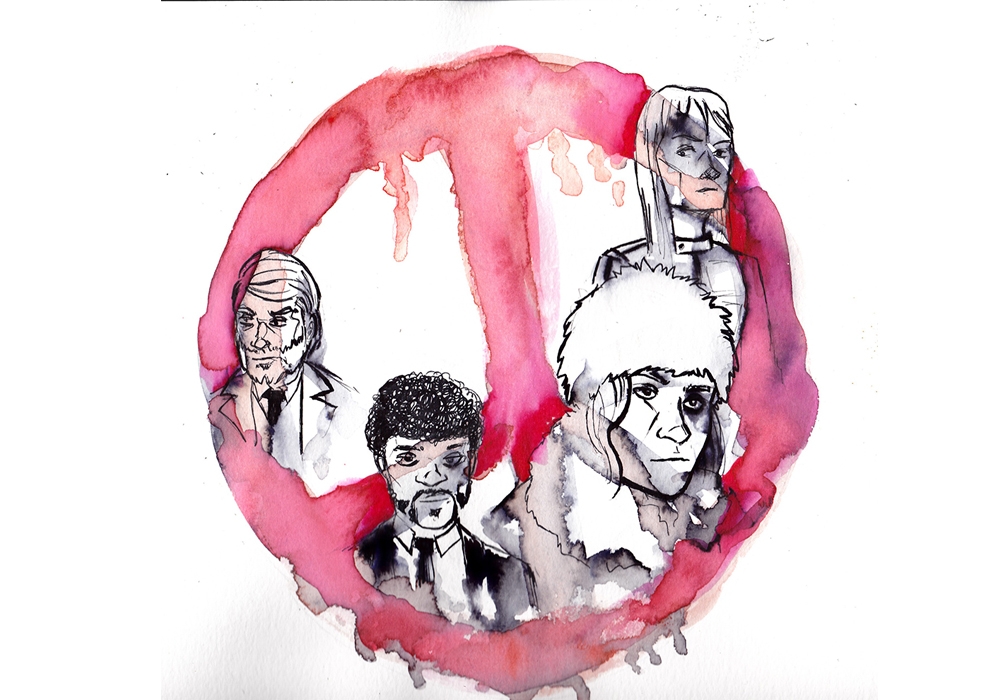

Featured illustration by Sophia Goshulak