Bernice Afriyie | Arts Editor

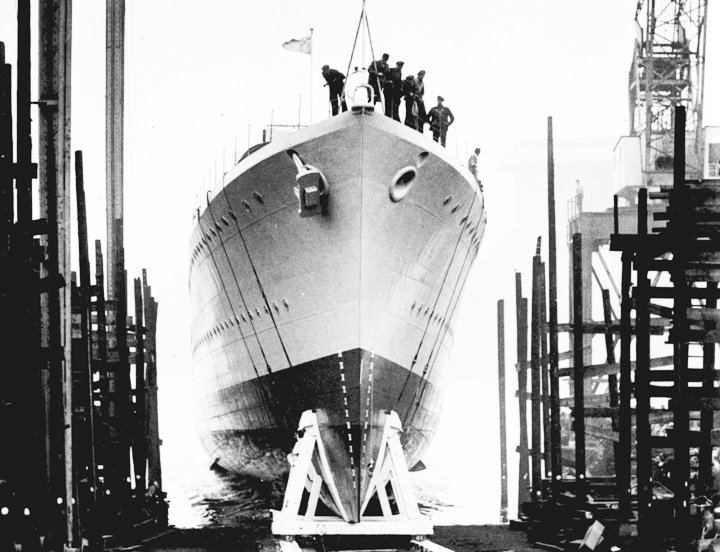

Featured image: The HMS Kelly, featured in In Which We Serve, was used in World War II. | Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

As the leaves change colours and we transition from fall duster coats to winter parkas, embellish our blouses and suits with poppies and remember Canadian soldiers who fought under the British monarchy, it seems natural that films and CBC specials on wartime Canada start popping up.

During World War I and particularly World War II, Britain needed to unite its homeland and sovereignties that were divided by race, class, patriotism and gender. Canadian and British propaganda films allowed the governments an affordable means to reach mass audiences at once. Pro-war beliefs and nationalism were sold to moviegoers as romances and adventures in films such as In Which We Serve, which was made during WWII with the assistance of Britain’s ministry of information. The films follows the HMS Kelly of the British navy, focusing on various members of the crew, all from varying British classes and ranks as each personal narrative speaks to British strength and patriotism in the face of adversity.

Such films suggested that every person, in direct relation to their class, race and gender, has a role to play and must do so. In effect, In Which We Serve was one of the most successful wartime films in uniting an entire Commonwealth under the British cause while still maintaining rigid social binaries. When WWII was long over, postwar films like The Colditz Story made sure that the Commonwealth clung to images of the monarchy’s glory and prowess during the war.

There are many arguments for whether or not the British government, and other countries for that matter, had the right to heavily influence public opinion of war. But regardless of the merit of the propaganda used during the wars, the films served their purpose without a doubt. Many of the government-commissioned war films were created to persuade public opinion, thus supporting the war effort.

Now, in lieu of Remembrance Day, we watch old war films, new war films based on the great world wars, films based on current wars and films based on fictional wars without stopping to ask what the point of all of this is. How does watching war films made for nationalism or entertainment honour the memory of fallen soldiers, or prevent more wars from happening? How does seeing elaborately staged war and gore scenes in sensationalized contexts warn against the horrors of war?

The pro-war films of the war era served their purpose in their time, whether they had the right to or not. They mobilized millions of civilians in a relatively short period of time. These films were not primarily concerned with artistic merit or challenging film conventions. Many wartime films created by the British government and viewed by the Commonwealth and ally countries during WWII made explicit their military motives by using actual war footage in their films, highlighting government sponsorships and displaying serviced military machines. As such, there’s no need to for us to rewatch or mindlessly recreate war films from the 1950s or 1960s. Continuing to reproduce and screen such films only normalizes images of terror, war and violence.

We need to ask ourselves what correlation, if any, exists between the British government’s desire to further its own cause through war films and remembering the millions of soldiers, civilians, nurses, doctors and prisoners of war who died.

If we really want to remember the men and women who died during WWI and WWII, read about them. Read the poetry they wrote, the lives they led before the war and the ones they hoped to live after the war. Consider the photographs taken in Canada by professionals and regular folk during the war. Educate yourself about the thousands of Canadians who disappeared or were forced into Japanese internment camps during WWII. Listen to the beautiful music that persisted in those dark times in spite of all the death, and edify yourself.