Abdeali Saherwala | Contributor

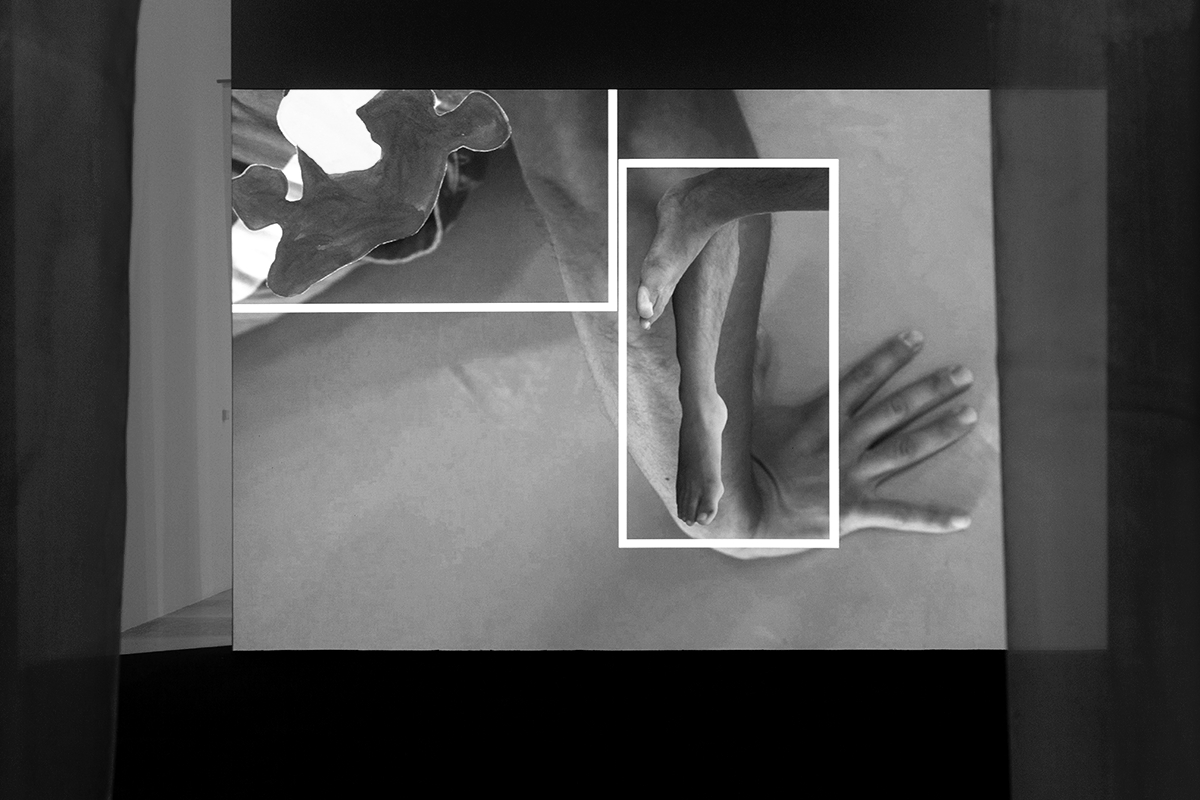

Featured image: The York exhibition allows visitors to experience movement through dance, theatre, and the visual arts, all in one visit. | Courtesy of the Art Gallery of York University

Some artists make art solely based on the stillness of an object or a view, while others are inspired by their fascination with movement. Artist Derek Liddington seems to be the latter. He created a solo exhibition around the performance of two photographic stills from the Ballet Russes’ productions of Ode and Apollon Musagète in 1928.

It is being staged back-to-back at the Art Gallery of York University (AGYU) in the Accolade East Building and the Southern Alberta Art Gallery. The exhibition at the AGYU is called the body will always bend before it breaks, the tower will always break before it bends.

Liddington’s new exhibition is a powerful and humanistic statement that utilizes 3-D clay caricatures and works imprinted or painted in fabrics and on walls. He also produced a video in which dancers perform in each other’s company, which is the product of a co-commission video shot by Toronto filmmaker Chris Boni. The short video was done during a time spent with students from York’s dance department in the summer of 2016. The dancing style used in the short is presented in a slow, graceful, and even an athletic manner, seeming to show the audience that the movement in dance is the embodiment of the intricacy of human movements, and the tensions of the human anatomy.

Not only that, it also presents the fluidity of our operativeness, despite our anatomy being constituted with rigid bones and firm muscles. Overall, Liddington shows the strength of the human form in an abstract manner.

The artist also makes sure that each exhibition uses the “performance still” (or production shot) as a dramaturgical framework for the development of its score and mise-en-scène. He attempts to capture the essence and authenticity of the Ode and Apollon Musagète, and not just to make art that looks aesthetically pleasing.

He makes sure that each gallery is a sample of Gesamtkunstwerk, wherein each component is operating at the intersection of dance, theatre and the visual arts. Liddington wants his audience to feel as though they have been to the theatre, an art gallery or dance performance, all in one visit.

According to Emelie Chhangur, the curator of the exhibition at the AGYU: “Liddington animates the space in-between performance and image as a point of departure for his ongoing investigation into the relations between narrative (meaning) and abstraction (aesthetics).”

He intends to cultivate a story out of his artwork. Audiences can interpret the drawings on walls and on free flowing curtains as symbols of the unlimited flow of the human body. We are free to move in any way we want, and yet, the marble sculptures represent load bearing joints of the human figure, and the clay sculptures portray our limitations in terms of movement.

With the exhibition, the audience doesn’t always get clearcut representations. It instead shows two sides of a story, which goes back to Liddington’s mission to intersect both meaning and aesthetics. He wants to create a world that displays both the significance of the body’s movement and our environment— in both positive and negative ways.

The main theme of this exhibition remains intact, being that the body will always bend before it breaks, the tower will always break before it bends.