Nicole Hanson

Contributor

Black enclaves – urban settlements with an inherent sense of both cultural and ethnic pride – are known for being separate from the societal social and economic mainstream. Little emphasis, however, has been set on their origins: a series of beginnings mainly built on race.

Both historically and presently, black enclaves have been a contested urban space. When we look at North American black enclaves – settlements such as Africville, Jane and Finch and Eglinton West – we are visibly engaging in spatial histories which may be unnoticed.

The births of these “ethnic enclaves” are imbued with strong, racial undertones that connect racial identities.

Looking back, black enclaves, such as Nova Scotia’s Africville, Vancouver’s Hogan’s Alley and Ontario’s Wilberforce Colony, have been nationally understood as an embodiment of black pride and community. Yet their formation was involuntary, because slavery and racism enforced lines of demarcation, drawing out an urban space for blacks to live and hindering them from settling in desirable spaces.

The forced nature of these black enclaves embodied oppression, because whites owned most of the land, exerted power and domination, and dictated where blacks would fit within the urban landscape – but these communities were nevertheless successful in building black solidarity.

Retrospectively, these spaces have fostered a sense of spatial emancipation and liberation from their white counterparts.

Now black enclaves are becoming voluntary spaces; the dynamics within them are liberating, empowering and uplifting, and build a sense of residential solidarity through community building.

Eglinton West and Jane and Finch stand as examples of community-building urban space in Toronto, Ontario. Eglinton West is called “Little Jamaica,” and is characterized by retail Jamaican shops, authentic Jamaican cuisine, barbershops and salons.

The black identities that make up this space have allied together to strengthen themselves as an economic, communal whole; however, the arrangement of these urban settlements, especially that of Jane and Finch, have become associated with stereotypes, clearly polarizing the city’s social, economic, political and cultural makeup.

That’s why Jane and Finch area has been labelled the home of the impoverished, disadvantaged or, more clearly, the urban poor, over-generalizing every identity within that space because they reside within that enclave. The politics of representation co-exist with the urban politics of the space when it comes to black enclaves, thus perpetuating not only an urban identity crisis, but re-instilling structures of hyper-segregation, racial discrimination and urban apartheid.

Black enclaves, whether thought of as voluntary or involuntary, are still oppressive, because as more blacks concentrate in these enclaves, they further remove themselves from the mainstream. What this mechanism does is reinforce a lack of economic opportunity, which continues to pave the way for both residential, community and entrepreneurial poverty.

The people in a neighbourhood reinvest their income back into their community. In situations of blatant poverty, neighbourhoods do not have that reinvestment coming back to them, stopping them from building the fundamental institutions that cater to community building. For the most part, the little sense of economic development these neighbourhoods once had quickly ceased; poverty creates crime, leaving the economic value of these businesses threatened.

Businesses thus move out of these areas. High insurance means businesses are forced to increase the price of their products, but the high crime rates do not allow for longevity and economic profitability, thus reinforcing discrimination and segregation, leaving the black enclave socially and economically stigmatized to development and growth.

Even though black enclaves are also seen as voluntary spaces, they continue to be the epitome of racial segregation and economic divide. They are notoriously characterized as unattractive spaces with a high rate of poverty. They are affiliated with joblessness, insurmountable teenage pregnancies, out-of-wedlock births (emphasizing discontinuity between black male and female relationships) and female-led families people assumed are welfare-dependent – and all of this against the backdrop of high crime rates.

Whether black enclaves are understood as involuntary or voluntary, these places have been sensationalized within the city. Black enclaves have become ghettoized, to the point where it’s almost taboo for blacks to live out in the suburbs. The ghettoization of these black enclaves perpetuates a sense of stagnation, affecting the identity of urban youth, both within the enclaves and outside of them.

Intangible structures such as racism, racial segregation and discrimination lead to urban segregation, and create a politic of identity that intentionally captures and emphasizes difference and limits social and economic integration for those identities within black enclaves.

This robs people in these spaces of the ability to create identities for themselves; instead, they become neglected, subordinate and dependent on dominant groups. If we can utilize this historic transfer – black enclaves premised on a racialized connectedness – then we can create a holistic approach to community building, not only visibly to the mainstream, but also internally, within ourselves, the foundation for a nationalistic sense of independence.

There needs to be a holistic approach to reclaiming the identity of our communities and to embody that nationalistic spirit of residential solidarity, community building and economic independency.

When we understand black enclaves were formed via a racialized connectedness, we can examine that shared history – a history of communities formed both involuntarily and voluntarily, premised not only in racism, discrimination and segregation but focused on community formation and restructuring.

This understanding will allow us to take better steps to form a nationalistic approach in rebuilding black solidarity within and outside black enclaves.

Nicole Hanson is the president of Apostolic Pentecostals of York University (APYU)

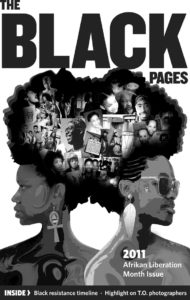

From Africville to Eglinton West