I dug my fingers into a tangle of thick wires that coiled around and bounced off my hand. This time felt different. My fingers weren’t running through straight, thin strands. I realized for the first time, at the age of 16, that my hair was growing.

I dug my fingers into a tangle of thick wires that coiled around and bounced off my hand. This time felt different. My fingers weren’t running through straight, thin strands. I realized for the first time, at the age of 16, that my hair was growing.

For years, I had chemically processed my hair. It had become a regular part of my routine. Every two months, as often as someone may cut their hair, I bought a box covered in smiling black girls with smooth, shiny straight hair, and relaxed mine.

The chemical burns were a naturalized exercise of my youth.

Stiff neck, sore scalp, silky hair: I went through the process without hesitation. I’d shiver when the first glob of white creamy crack tickled my scalp; my mother’s hands were always smooth and precise.

It seemed to be a rite of passage for every black girl to shed her kinks and coils as she entered into adolescence.

I only knew that something undesirable and unacceptable came out of my scalp and needed to be kempt and suppressed.

But then I wonder why this limited view of beauty, being defined as Eurocentric, has maintained itself for so long, especially in our “free” nation of Canada, hundreds of years after slavery’s abolishment?

In commercial campaigns for hair products like Pantene, Dove, Garnier, Herbal Essences, and others, the women are always white with long, silky, wavy, shiny hair, and if the token black woman does appear, she hides in the fringes of the shot, most often dressed in loose curls, permed hair, straight wigs or blond lace-fronts. A black woman rarely appears as she is.

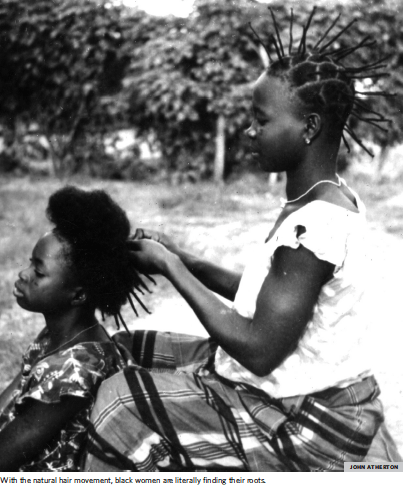

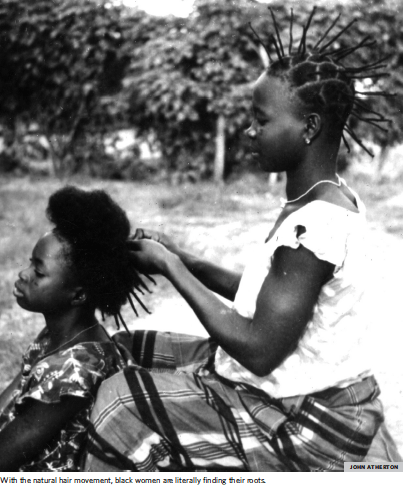

Black women in schools, workplaces, and the media are still judged by the same Eurocentric standards, but things are slowly shifting. An increasing number of black women in Western countries are choosing not to chemically process their hair.

When I was growing up, every black woman I knew either had a relaxer, weave, or wore a wig.

Now, on a bus in Toronto, I see more women sporting puffs, Bantu knots, afros, and twists.

Black women are literally finding their roots. They are dealing with what is, as opposed to beauty’s preoccupation with what can be, and this doesn’t necessitate a “good or bad” or an “either-or” relationship.

Straight hair doesn’t become a sign of inferiority and curly hair a sign of dominance: all hair is good. The natural hair movement permits more than one kind of beauty to exist.

This isn’t a superficial trend that will pass next year; it can be seen as the narrative of a black race reaching its liberating climax.

Some may make the argument that hair is trivial.

Hair doesn’t matter and celebrating the specific features of a race perpetuates the distortions of beauty, that black women wearing their hair naturally only succeeds in displacing and replacing the dominant view.

But when society twists and uses your physical, biological attributes against you as a sign of your inferiority, when beauty companies effectively edit and eliminate your features, it is oppression.

Hair is made trivial to mask layers of exploitation, and attention is taken away from the seriousness of the issue.

Why is the notion of having hair that naturally forms an afro so absurd? Afros have become extreme hair styles, accessories in costumes. The afro, removed from its place in the everyday, is put in the realm of the garish, quirky, and outdated.

Who hasn’t laughed when a white man dressed in a huge afro, pink sunglasses, disco shoes, and flashy clothes twirled his arms and shook his butt?

After years of not knowing our hair, I think we are justified in showing off our coils and kinks. Only when natural hair becomes the norm, and not the exception, can it move from being a necessary point of emphasis to a trivial part of the body.

Because of the natural hair movement, it won’t matter that my hair is coily and someone else’s is straight. My hair will reclaim itself as a bodily feature needing no more fixation than an ear.

We need to relax our notions of what is acceptable, for hair doesn’t divide itself into kinky, straight, or curly. Hair is textured by our beliefs.

Bernice Afriyie

Contributor