Eleanor Higginson, Staff Writer

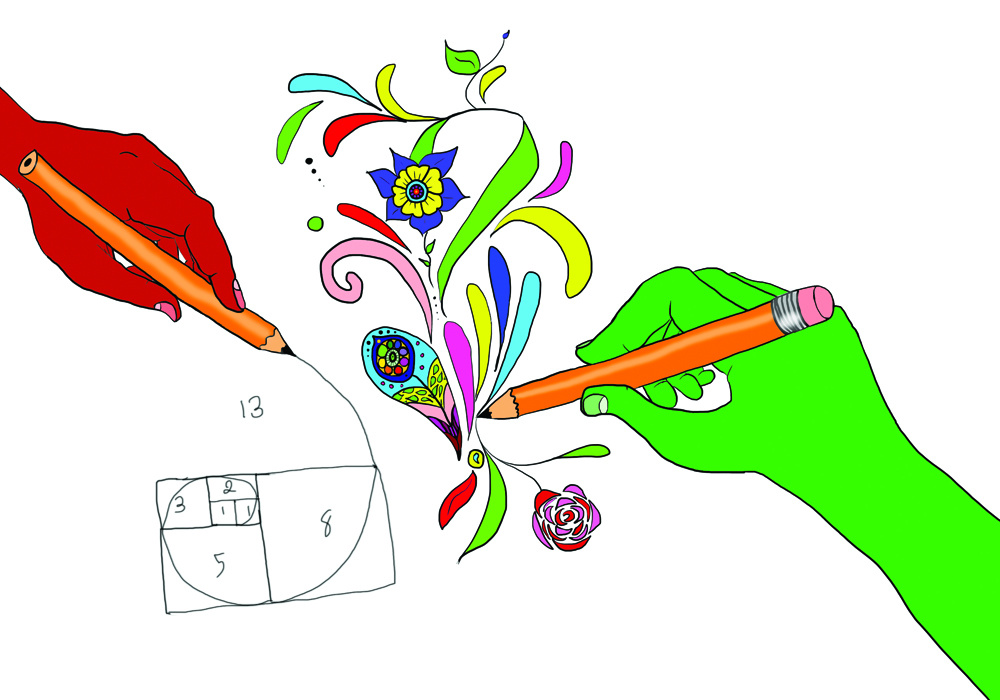

Featured image courtesy of Krystaleah Ramkisoon

I’ve always been particularly proud of being left-handed. Whether this came from being the only left-handed member of my immediate family, or from the instances of real-life “discrimination against left-handers” that I can testify to have experienced, I’ve always been excited about research that proves that we really are just more intelligent, creative, and perceptive than the common right-hander.

Famous left-handers include five out of the last seven United States presidents, and a number of highly influential figures such as Wolfgang Mozart, Bill Gates, and Oprah Winfrey. But circumstantial evidence and my personal bias aside, how much do the various claims about left-handers perpetuated on the internet, ranging from the positive “more likely to be a genius” to the negative “more likely to commit suicide,” really hold up?

As a simple Google search reveals, there is undoubtedly a great deal of interest in the supposed special abilities of left-handers. And there does seem to be a certain amount of scientific evidence behind the popular psychology. As reported in The New Yorker in 2013, a University of Athens study involved inviting a group of university students, half of them favouring each hand, to complete two versions of the Trail-Making Test, in which “participants had to find a path through a batch of circles as quickly as possible.”

In both versions of the test, one easier and one more complex, the left-handed group consistently demonstrated “faster and more accurate spatial skills, along with strong executive control and mental flexibility” as well as “enhanced working memory.”

Even more strikingly, “the more intensely they preferred their left hand for tasks, the stronger the effect.” There is also ample evidence behind the oft-repeated assertion that left-handers are more creative and independent thinkers.

Academic Chris McManus of University College London, has argued in his book Right Hand, Left Hand: The Origins of Asymmetry in Brains, Bodies, Atoms and Cultures that the very structure of left-handed people’s brains, as well as genes which cause left-handedness, mean that left-handers can approach a wider range of tasks in more esoteric ways than right-handers.

Yet it is not as if left-handedness is without its fair share of negative stereotypes. In fact, the very Latin root of the word for left, “sinister,” took on the additional meanings of “evil” or “unlucky,” whereas the word for right, “dexter,” means “skill.”

Although it seems laughable now, left-handedness was once considered by criminologists and psychologists to be a strong indicator of mental, moral, and emotional disturbance. This was not even particularly long ago: for instance, in 1977 the psychologist Theodore Blau referred to left-handed youngsters as “sinister children” whose preferred hand caused them to be more likely to suffer serious mental health issues, such as schizophrenia.

Anecdotal stories about left-handed children being sent out of the classroom until they had resolved to be right-handed or even beaten for their difference occurred a shockingly short time ago.

Nonetheless, some of the difficulties that left-handers face may not just be caused by prejudice. For instance, psychologists have found that left-handers sometimes tend to congregate more around the extreme ends of the spectrum, making them just as likely to be at the lower intelligence end as the average right-hander.

Despite all this evidence that there may in fact be some differences between the brains of left-handers and right-handers, with some of them working in favour of left-handers and some of them not, I cannot help being a little skeptical about those who claim that the hand you happen to favour has a significant impact on your life.

For one thing, handedness is not binary: a fact which I can personally testify to, since I’ve often fretted that because I prefer to play tennis with my right hand, despite the fact that I do almost everything else with my left hand, I am not a “true” left-hander. Although few of us are perfectly ambidextrous, I would argue that the vast majority of us use both hands to some degree, or could easily learn to with a bit of practice.

Moreover, many right or left-handers prefer to use the opposite foot, or find that their ear or eye on the other side is stronger. It also appears that this is the direction that scientists are swinging in now, recognizing that just as in the past left-handers were unfairly demonised, so too have they more recently been ridiculously praised.

It is also now thought that the cognitive advantages that left-handers generally possess over right-handers do not come from any innate superiority, but from being forced to develop the use of their non-dominant hand due to the fact that the world was built for right-handers. So I’ll continue to advocate for left-handed pride, but the secret of our success may lie more simply in that good old-fashioned proverb of “practice makes perfect.”

Follow us on instagram, @excalphotos