Jodie Vanderslot | Staff Writer

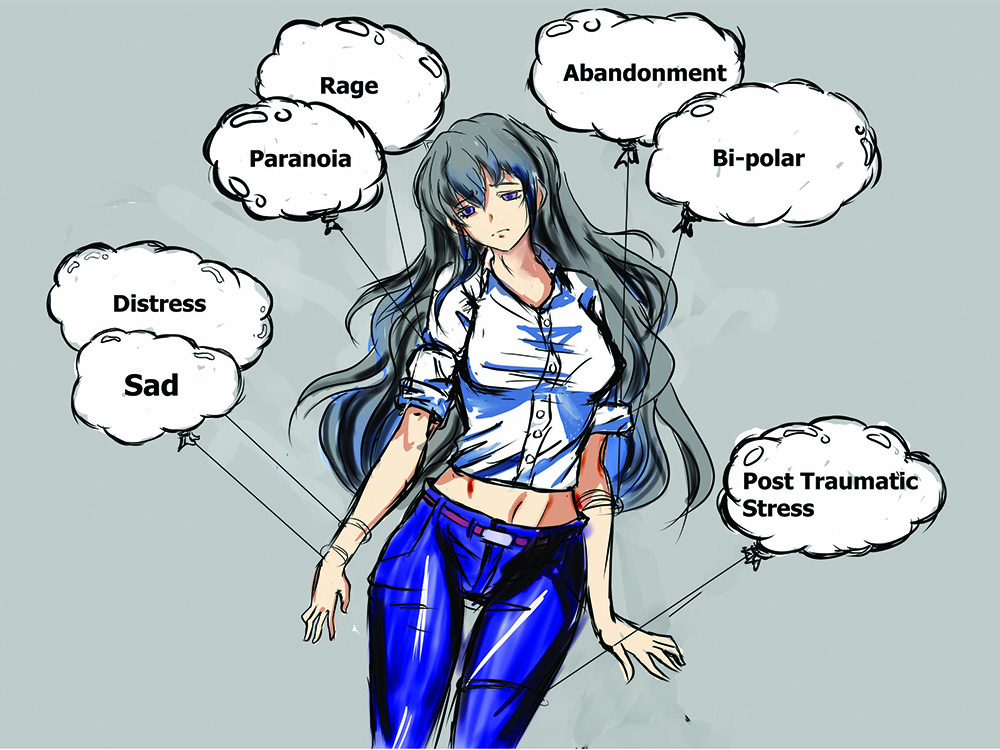

Featured illustration: Casual expressions using mental illness, rather than emotions, can work in undermining mental illness. | Cedric Wong

As individuals and as a community, we find ourselves frequently mislabelling our emotions. Every day, we experience a myriad of emotions, a tirade of thoughts that are constantly rolling in our heads. We convey them through our actions and words, and sometimes a lack thereof. We need to develop a vocabulary that more discriminatively expresses these states and conveys the feeling we are trying to express. When we think of depression as synonymous with sadness, or being nervous with an anxiety disorder, we minimize the illness and severity for those affected and diagnosed.

Mental illnesses are unique lived experiences that affect everyone differently; we don’t always realize the many other debilitating symptoms they create. It can be considered offensive, as well as medically and politically incorrect, to use mental illnesses as a descriptive term nonchalantly. Mental illnesses are not adjectives, metaphors or hyperboles—they are diagnoses.

Claiming you are depressed when you find out your favourite show is cancelled, announcing that you are having a panic attack because you’re nervous before a presentation or that you’re OCD about how you like your room represent a lack of awareness in the language we use around mental health. What you mean is that you’re irritated, you’re worried or you like things a certain way.

The use of mental illnesses in the form of phrases have become so common in our conversations that many of us fail to even acknowledge their presence. If someone is really expressing their depression, it should evoke concern and empathy. These phases undermine the all-too-real impact of mental illnesses, and using these words so casually implies that they are ways of acting, rather than real illnesses or symptoms.

“If someone does have a particular diagnosis, it is not trivial. [The diagnosis] implies that there is an impairment in functioning and an incredible amount of suffering. Illness shouldn’t be taken lightly,” says psychology professor Myriam Mongrain.

“This terminology was intended to refer to a problem […] The way people use the language now is like there’s not an actual problem.”

Mongrain’s research focuses on personality vulnerability to depression and positive psychology interventions.

Being sad, upset or nervous are all valid feelings and appear regularly on the spectrum of human emotion and behaviour. There needs to be a distinction between emotions and their degrees of severity. It is important to recognize these degrees, as well as the vocabulary that goes along with them.

Mental illnesses, such as depression, are emotions that are experienced for an extended period of time. It is a pervasive sadness, usually extending over at least two weeks, compromising an individual’s ability to adequately cope.

“The proper use of the word comes with an impairment in functioning […] You are just not able to meet the responsibilities of your day-to-day activities. There is distress. The person is unhappy; the person is suffering and usually for extended periods of time,” explains Mongrain.

Sadness is specific in its cause and distinguished by knowing the source, such as a loss or failure. Knowing the context will help one determine a solution to the feeling.

“We have these negative emotions as a reaction to something that has happened, either perceived or real.

“When the person is able to label their emotions a little more correctly, a little more specifically, there is an answer already in pinpointing the right emotion. Feeling sad can refer to missing something […] and if you’re able to say you miss emotional support, you miss the connection […] there is a relief that comes immediately from knowing what it is that you miss and what you need,” adds Mongrain.

“Depression then, is when you’re not able to be clear within yourself or what would help to make it better.”

When we speak of any mental disorder outside of its intended context, we are breaking the illness down to its simplest form: the stigma and stereotypes it is most commonly associated with, which, more often than not, are wrong. Mental illnesses are not metaphors or terms meant to exaggerate or emphasize a point, nor are they similar to the medical condition.

To the people affected by that diagnosis, the symptoms are very real and debilitating. We need to be thoughtful with our words and more aware of their meaning. Once we correct our perception of mental illness, our vocabulary should align.