Matt Dionne | Sports and Health Editor

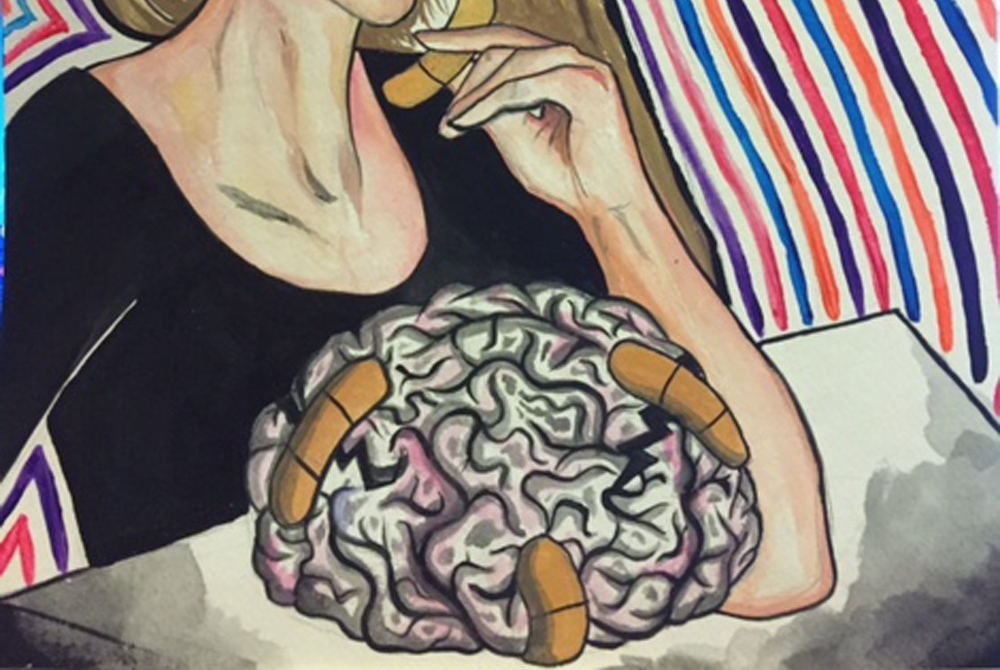

Featured illustration: Researchers are trying to find more than a band-aid treatment for concussions, including better prevention tactics. | Maya Belson

If you’re a sports fan, you’ve probably heard of players being sidelined with concussions. Perhaps you’re a fantasy sports enthusiast, and have had to adjust your lineup because one of your starters was knocked out with a concussion. Or maybe you just really like Will Smith and saw the 2015 film.

But what is a concussion?

Concussions, often referred to by athletes as the c-word, are traumatic brain injuries usually caused by hits to the head.

Other injuries are fairly easy to detect—if you break a bone, for example, there is usually a visible indication of the injury, as well as an incredible amount of pain. But concussions are an invisible injury, and are harder to detect.

Fortunately, advancements in technology and increased research have allowed us to learn more about the nature of concussions.

A recent study by Purdue University found that concussions are possibly caused by multiple hits to the head over time, as opposed to the previous notion that they were caused by a single impact. Another common misconception about concussions is that they go away after a certain amount of time, without any lingering side effects. In reality, many people who experience concussions also experience post-concussion syndrome, where symptoms last for more than six weeks.

But what are the symptoms, and how do you know if you have a concussion? According to Mayo Clinic, symptoms include headaches, loss of consciousness, dizziness, nausea, vomiting, confusion, fatigue and slurred speech.

In severe concussions, a person’s pupils may appear different sizes, with one dilated more than the other.

Some symptoms may take longer to show up, such as memory loss and an inability to concentrate, irritability and personality shifts, sensitivity to light, erratic sleeping patterns and even psychological disorders such as depression, according to Mayo Clinic.

More alarming are the findings by the researchers at York’s Centre for Vision Research, who found that athletes who suffer concussions may also have neurological deficits that are typically not detected in standard clinical assessments.

The study compared the cognitive-motor integration between 51 athletes who had never been diagnosed with a concussion, and 51 athletes who had a history of concussions but were no longer showing symptoms.

The goal of the study was to determine whether athletes with a history of concussions displayed any impairment when asked to “think and move at the same time.” Participants were asked to perform two separate tasks that tested their cognitive-motor integration.

According to the results, athletes who had never suffered a concussion performed the tasks roughly 50 milliseconds faster than athletes who had.

While that doesn’t sound like a large difference, it could be the difference between getting hit or not, according to Professor Lauren E. Sergio.

These tests could also provide a more accurate assessment for determining when a player is safely able to return to the field or rink. If a player returns to their sport too soon after experiencing a concussion and suffers another, known as second impact syndrome, the results could be devastating and even fatal.

Side effects of second impact syndrome include swelling in the brain, possible herniation, loss of consciousness, acute metabolic changes and cerebral blood flow alterations, according to brainandspinalcord.org.

Hopefully as we learn more about the brain and how it functions, we can find ways to ensure player safety and better diagnose concussions—or prevent them from happening at all.