Paul Burd

Contributor

A whopping 1,235 possible planets, including five Earth-size planets capable of supporting liquid water: a startling discovery, presented at a widely anticipated NASA news conference Feb. 2. That’s the day the space agency announced its planet-hunting Kepler telescope had gained traction and delivered astronomers a significant boon – the first planets ever discovered that could harbour life.

These results, based on just four months of observation, rival earlier searchers for exoplanets, planets outside of our solar system, in both scope and significance. Kepler is weighing in late in the game, as the first planet detected outside of our solar system was confirmed in 1995.

A Jupiter-like gas giant seared by its close proximity to its star, this discovery ushered in a wave of many similar planetary discoveries that’s left the list of confirmed planets at just over 500. But astronomers hoping to find another Earth were disappointed when many more such “hot-Jupiter” planets, in which the crushing gravity and intense heat would prevent the conventional formation of life, came to dominate their planetary census.

Astronomers now believe this high gas giant ratio is due largely to a bias in method. Most of the planetary discoveries made before Kepler used the radial velocity, or wobble, technique, which involves detecting the small gravitational tug made by a planet on its star.

“Big planets close in are going to give a bigger influence; therefore, we were seeing them first,” explained Paul Delaney, York’s observatory director.

To bypass this problem, Kepler uses the transit method: constantly watching a field of 156,000

stars since May 2009, Kepler’s camera is poised to detect the faint drop in starlight caused by a planet eclipsing its star from our perspective. These mini-eclipses, called transits, allow astronomers to measure the size of a planet, and their frequency determines how far away they orbit their stars.

In choosing the transit method and applying it to so many stars at once, the Kepler science team is aiming to balance out our early picture of massive exoplanets with a surge of smaller worlds.

“We had hoped that Kepler would begin to fill in that end of the mass spectrum, and it has,” Delaney said of this latest data release. Indeed, some of the smallest planet candidates ever detected were announced at the news conference, including 68 that are approximately Earth-size or even smaller.

The Kepler science team is referring to these discoveries as “planet candidates” until they can be confirmed with ground-based telescopes, but independent analysis by other astronomers has determined that as many as 90 percent of the 1,235 discovered candidates are actual planets. In a boost to the creditability of this approach, NASA announced in January that they had used ground-based observations to confirm the existence of a planet just 1.4 times the size of Earth. Called Kepler 10b, this planet holds both the record for being the smallest exoplanet ever found and, with a density around that of iron, the first exoplanet discovered that is indisputably rocky.

Diversifying our picture of exoplanets even further is Kepler’s discovery of 170 solar systems with more than one planet. The Kepler science team, with bravado normally uncharacteristic for astronomers, has even confirmed the largest of these systems: with six planets all orbiting closer to their star than Venus is to the Sun, the Kepler 11 solar system boasts the most planets ever discovered around another star.

The gem of the data release, however, is certainly the five Earth-size planet candidates found orbiting within the habitable or “Goldilocks” zone of their stars, a region neither too hot nor too cold but just warm enough for liquid water to exist on the surface of a rocky planet. These results bode very well for the search for life, as these kinds of planets are thought by astronomers to be the ideal incubators for its initial formation and support.

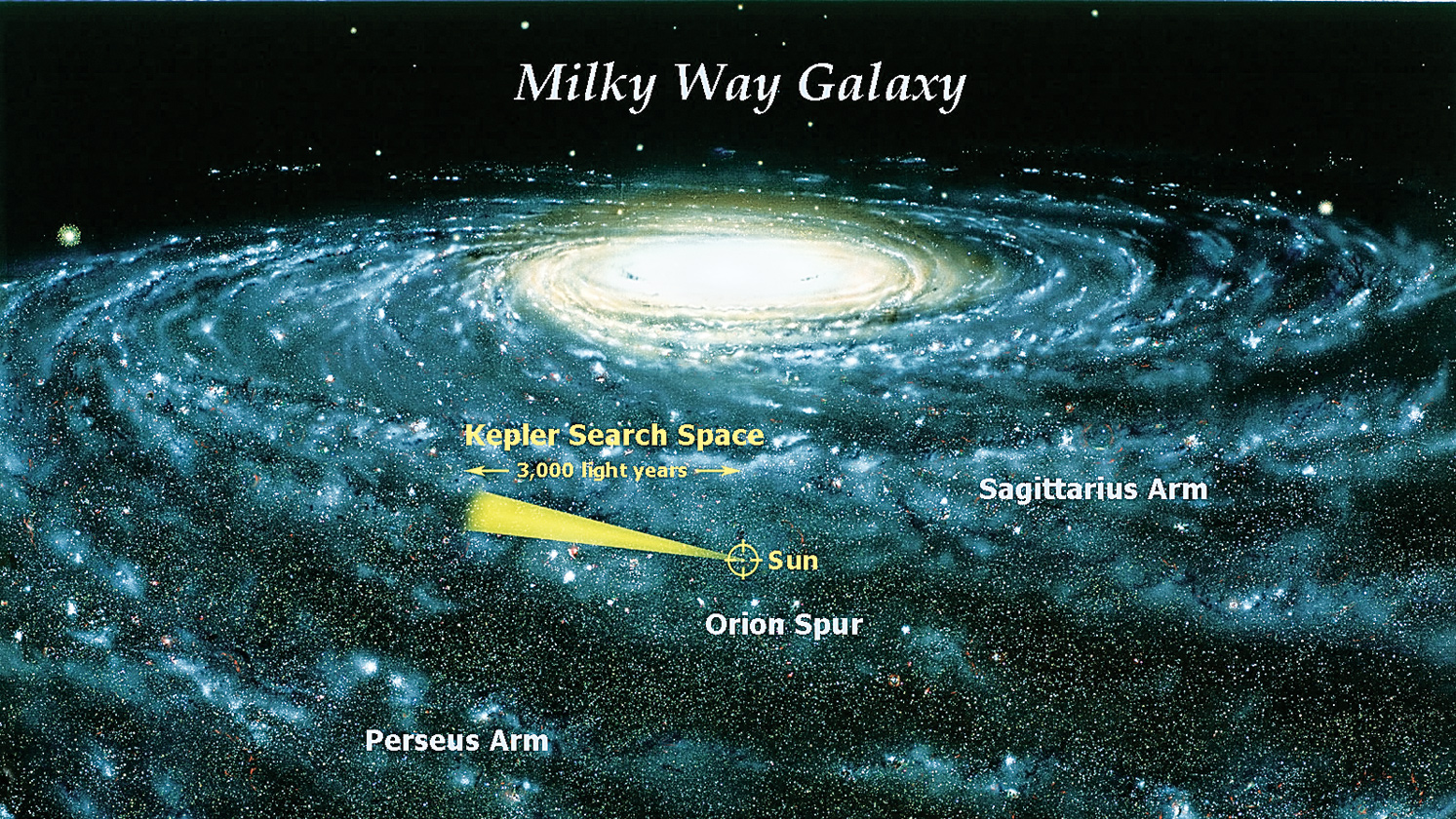

This discovery is also a boon to the statistical chances of finding alien life, as these planets likely represent a very small fraction of the Earth-like planets in our Milky Way galaxy. Considering that Kepler is observing a relative sprinkle of our galaxy’s 300 billion stars (somewhere in the neighbourhood of 0.00003625 percent) Delaney argues these five planets are merely the tip of a very large iceberg. “When you scale up […] tens to hundreds of thousands at a minimum are being suggested,” said Delaney.

Looking at this huge jump in habitable exoplanet real estate as just one step in their search for alien life, astronomers are already brainstorming ways to use Kepler data to produce the smoking gun.

Dr. Marshall McCall, the director of York’s department of physics and astronomy, argues these five exoplanets should be targets for radio astronomers.

“The real groundbreaker from that standpoint would be to detect radio signals, like coherent information,” he says.

Project SETI (Search for Extra-terrestrial Life) looks for radio waves that could be coming from alien life-forms in the galaxy; they’ve been patiently listening to the stars for years without a signal, notes McCall, but the stars Kepler singles out as having habitable planets can now serve as targets for a more directed search. Astronomers are also honing their ability to probe the atmospheres of exoplanets by analyzing the light that passes around them during transits. Once this method is refined, says McCall, it may be possible to confirm life indirectly by detecting the telltale traces of oxygen, methane or ozone in an Earth-like planet’s atmosphere.

Considered the “holy grail” of exoplanet searches, astronomers are hopeful Kepler’s results will point us toward a planet that harbours alien life. With over three years of data yet to be released, Kepler’s planetary census has only just begun, but the truly significant contribution of this mission will be its answer to a timeless question: How common are planets like Earth? It is very likely that NASA’s Kepler Mission will make ours the generation that finally answers this question. For the moment, astronomers are waiting with bated breath for confirmation that our planet is but one blue marble in a vast galactic ocean of other life-friendly planets.

The search for the earth look-alike