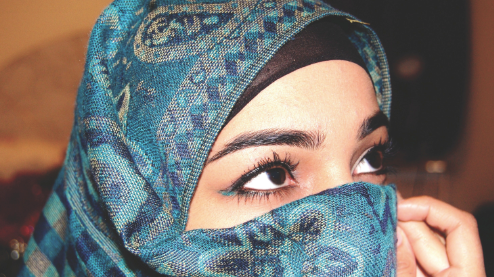

Ruqaya Ahmed reflects on the politics of terrorism, and living as a Muslim in the aftermath of 9/11

Ruqaya Ahmed

Contributor

A few months ago, I was sitting in a packed subway train when I noticed the middle-aged woman beside me shooting me a few apprehensive glances. Chalking it up to curiosity over the fact that I was wearing a headscarf, I gave her a friendly smile and continued reading.

But about a minute later when I opened my bag to retrieve a water bottle, something strange happened. The woman’s face immediately drained of color; her expression became that of utter dread. She quickly stood up and moved as far away from my seat as she possibly could.

I was completely flabbergasted. What did she possibly think I carried in my bag that made her react like this?

It wasn’t until the subway doors had opened and the poor woman bounded off that I came to a grand realization—I had opened my bag and in that sliver of a moment, the woman realized how similar I looked to the images of suicide bombers and “jihadists” she’d seen on television. I don’t blame her—fear turns us all into irrational creatures—but in encounters like this, I am reminded over and over again how much things have changed since the September 11 terror attacks.

Ten years have come to pass since that ill-fated morning, and the wounds are understandably still fresh. But we have become a culture driven by hate, suspicion, and fear. And because I am visibly identifiable as a Muslim—a religion I share with the alleged hijackers of Flight 11—I am that scary, suspicious thing. I am 19 years old, and I am a stranger in my homeland.

If that woman on the subway had delayed her fear for a few moments, she probably would have realized that I was about as equal a threat to her safety as was the man with the construction helmet dozing nearby, or the woman in Birkenstocks chatting on her cell phone. Terrorism is not limited to a specific, race, religion, appearance, educational background, or social class. But if our increasingly politicized and propagandized media programming is any indication, the War on Terror has become a War on Islam.

It is true that some people have committed heinous crimes in the name of Islam. However, their actions are never justified or endorsed by upright Muslims who embrace and preserve the true spirit of Islam.

The sacred position of human life is clearly delineated in the Holy Quran: “If anyone slew a person […] it would be as if he slew the whole people. And if anyone saved a life, it would be as if he saved the life of the whole people” (5:32). But when politicians or media outlets continuously refer to those responsible for 9/11 as “Islamic terrorists” instead of simply “terrorists,” they give a false impression that such crimes actually have a place in Islam.

The term “holy jihad” is also repeatedly taken out of context by the media in an attempt to explain the motive for such crimes. Literally, jihad means to “struggle or strive,” be it on a personal level or against oppression. Accordingly, the use of armed warfare to defend against persecution is permitted in Islam, but it is forbidden to harm those who seek protection, such as common civilians, women, children, and the ill (Quran 9:6). An act of terrorism against the innocent and unsuspecting civilians is exactly that: an act of hirabah (terrorism) that has nothing to do with holy jihad.

Islam cannot be blamed for the 9/11 attacks any more than Christianity can be blamed for the actions of the KKK or the IRA, or Judaism for certain radical Zionist groups in Israel. The media did not use the term “Christian terrorist”, or “Jewish terrorist”, or “Hindu terrorist” when referring to Anders Behring Breivik, Baruch Goldstein, or the Tamil Tigers; responsible for the Norway attacks, the Cave of the Patriarchs massacre, and the Digampathana truck bombing, respectively—and rightfully so. It is unfair to tar all the people that belong to a certain faith with the same brush.

But when Bill O’Reilly takes a seat on The View and says that a Muslim community center should not be built near Ground Zero because “Muslims killed us on 9/11”; when CNN abandons all journalistic integrity and broadcasts a “live shot” of Arab civilians celebrating the 9/11 attacks—actually footage taken in 1991 when Palestinians were celebrating the Scud attack during the Gulf war; and when calling Barack Obama an Arab becomes a “smear campaign” whereby John McCain must rush to assure us that “Obama is not an Arab. He’s a decent man,” it gives mainstream North America a false impression that all 1.6 billion Muslims across the world are violent heretics and that “Arab” and “decent” are truly antithetical to one another. Biased as these viewpoints may be, political media shapes public perception. And the result has been a rise in state-sponsored Islamophobia and Anti-Arab sentiments.

It is only human nature to hate that which you fear, but hatred is also the root cause of criminal violence. In the wake of the 9/11 attacks, CNN reported several incidents of harassment and hate crimes against Muslims and people of Middle-Eastern appearance. After 2001, both the FBI and Canadian Islamic Congress reported a 1600-per-cent increase in hate crimes against people perceived to be Muslim in the United States and Canada.

I remember going to the grocery store a few days after the attack

and being called a terrorist at the age of nine by a grown woman. I remember walking to school or the park and being told to “go home, sand nigger.”

I don’t claim to have suffered more than anyone because of 9/11. There are people who lost their lives or their loved ones in those burning buildings, people who deserve our prayers and deepest sympathies. But we must also realize how cruel it is to hold children accountable for crimes they haven’t committed. Until the morning of 9/11, I was a scabby-kneed fourth grader who loved to read Beezus and Ramona. By evening, I had become an enemy alien.

It is frustrating to have to deal with so much ignorance and intolerance each and every day. It is frustrating when you take a summer vacation to New York and find that the white family in front of you can pass through customs in five minutes flat; but there you are, 15 minutes later, wondering if you’re going to have to turn around and make a seven-hour trek back home because you are now on some kind of no-entry list. It is frustrating to have your religion questioned and attacked on a daily basis in newspaper headlines while media outlets virtually ignore the story of 63-year-old Roger Stockham, who stocked his van with explosives and drove to Detroit on January 26, intending to blow up the state’s biggest mosque. It is hurtful when your next-door neighbour, whom you have known for the past twelve years, suddenly stops speaking to you.

I recently read an article written by American citizen Jennifer Young for the Al-Waref Institute, where she talks about encountering a poster called “The Faces of Global Terrorism” in an airport. She notes that all of the photographs on the poster are of men who share similar “Middle-Eastern” characteristics: some with turbans or long beards, all with Arab last names. Like any decent human being, she is outraged by this poster because it attempts to stereotype and generalize a “cross-section of individuals as terrorists.”

Personally, I think the images on this poster have gone rather stale from overexposure. What this poster needs is an influx of fresh new faces. And as far as suggestions go, why don’t we ask people who actually come face-to-face with violence and terror every day of their lives?

Why don’t we ask the family members of the 8,813 innocent Afghani civilians and the 864,531 innocent Iraqi civilians killed in Bush’s “War on Terror” whose faces they think should be on the poster?

Or we could ask the families of the hundreds of Libyan civilians killed and injured by NATO airstrikes, which were conducted for the sole purpose of “protecting civilians” and assuredly have nothing to do with vast oil reserves conveniently lying underfoot.

While we’re at it, why don’t we also ask for input from the four million or more displaced Iraqi civilians whose lives have been upturned by the US government’s feverish search for those oft-heralded “weapons of mass destruction” that also have nothing to do with assuming control over the world’s largest oil pipeline?

It’s a shame that the dead can’t talk, or we could have asked opinions of the three blameless children who were gunned down by NATO airstrikes in Gadhafi’s compound as the world sat by, unperturbed.

What our politicians need to realize is that when you set one human life over another, when you allow the murder of innocents to go by unannounced and then try to euphemize these murders as “collateral damage,” you become complicit in the same acts of terror you waged a trillion-dollar war against. Maybe we should use mirrors instead of telescopes the next time we try to identify the faces of global terrorism. And maybe, just maybe, we’ll be that much closer to winning the war on terror.