Brendan Rowe

Contributor

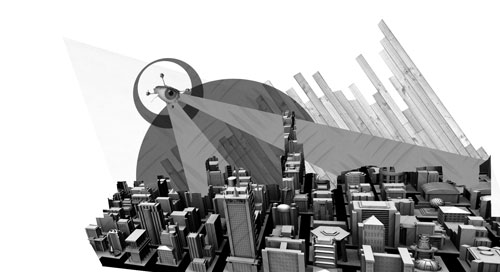

York researchers are bringing urban maps into the third dimension.

York professor James Elder is project lead of a multi-university team developing new surveillance approaches in an urban landscape.

York professor James Elder is project lead of a multi-university team developing new surveillance approaches in an urban landscape.

The project, “Three-Dimensionalizing Surveillance Networks”, is organized by the GEOIDE Network, a partnership between governments, universities, and industries. GEOIDE stands for GEOmatics for Informed Decisions and it promotes and funds geomatics projects in Canada.

Elder’s project tries to bring the processing and handling of geographic information into the future.

As part of this larger mission, scientists flew an unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) around Keele campus over the summer. It was part of an experiment to develop technology for 3D modelling of urban environments.

Elder leads a team of researchers from UBC, U of Calgary, Waterloo, McGill, and Carleton. They want to merge computer visual sensing with 3D models of urban environments. By doing so, they can better understand and visualize what’s going on in our cities.

The project has implications for urban security but Elder says security is not necessarily the first application of the research. There are many applications of UAVs and 3D mapping. However, Elder explains, the technology could replace common 2D camera surveillance systems in cities.

“[Security] cameras are two-dimensional,” says Elder. “We want to be able to take information from that two-dimensional view and infer what must be going on three dimensionally so that we can show that to an observer on a screen.”

They’re interested in “multi-view reconstruction”: how can we get 3D structure from a sequence of imagery?

In an institution with several buildings and complex topography, Elder explains, it’s hard to figure out what’s going from a wall of security TV monitors.

“They’ve done the experiment where they replayed [an emergency] scenario in a three dimensional visualization. It’s very compelling […] It all becomes clear.” A full 3D view makes that visual information easier for an observer to interpret and take the correct steps. Safety becomes less of a concern when less mistakes are made in an emergency.

A constructed 3D view requires many different data inputs, provided by a UAV like the Aeryon scout. A UAV can fly at different altitudes and into small nooks and crannies. Elder says it can see things potentially that can’t be seen from other angles.

The Scout is a little different from its UAV counterparts. Its small size and propellers allow it to approach buildings most fixed-wind UAVs cannot.

The Aeryon Scout was instrumental in the iCampus Project, led by York researcher Gunho Sohn. Over the summer, Sohn used the Scout’s imagery to build a comprehensive 3D model of York’s Keele campus.

The next step is to use that 3D model and be able to embed dynamic activities of objects in the model. “That’s a major step forward to be able to not just have a static model” Elder says. The research done on the iCampus Project has since been added into the bigger project as they move ahead.

UAVs and 3D modelling could likely be used by medium-sized institutions, like nuclear power plants or high security political institutions, Elder says. It could be useful anywhere where’s there’s a real risk and a desire to respond quickly in a crisis.

“If there’s ever a crisis, a small electric UAV [could] be deployed by an institution like York to quickly find out what’s going on,” but the team didn’t explore that possibility in the iCampus Project.

Elder thinks private institutions will see the value in the research. They can integrate the 3D data into with intelligent building systems that conserve energy or maintain security. An entire facility could be integrated into one 3D model.

There’s no question, Elder says, that in the future more of our media will be delivered to us in three dimensions: “we experience the world in three dimensions, that’s just the way we’re built.”

He’s interested if this kind of technology becomes available to private citizens and harnessed into the internet. “We’ll have three dimensional visualizations of what’s going on [in the world] and there’ll start being live more often.”

However, privacy becomes a concern once the technology is introduced to the public.

“We suggested [that] by iconifying or virtualizing people in cars as avatars, you may then have sufficient protections on privacy.”

By transforming people into avatars, you wouldn’t be able to identify them. This might not be enough.

“I think it’s okay,” Elder says, but it can be argued a certain amount of privacy is being violated by remotely observing someone’s car. Someone might recognize it.

Using UAVs to map our world in 3D will change the way we interact with our cities. The technology can also help us build a smarter city. It will help us gather data about our cities and visualize them in compelling ways.

Dr. Elder urges caution. “I hate to downplay it, but [the experiment over the summer] was an exploratory activity.” The smarter city is the lofty goal, he says, but it’s going to be a long time before they achieve it.