Richard Dawkins’ new controversial book calls religious origin stories “myth”

Steven Arrol

Contributor

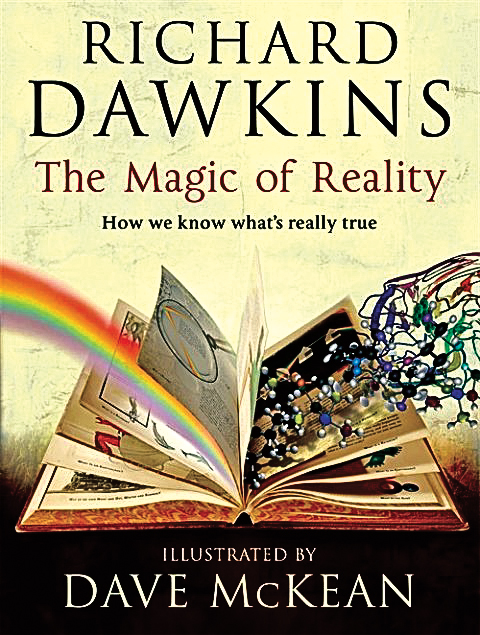

Richard Dawkins’ latest non-fiction offering, The Magic of Reality, aims to educate children about everything science-related, from the distant corners of space down to the smallest building blocks of our DNA.

Accompanied by fully-coloured illustrations from artist Dave McKean, Dawkins explains topics as varied as the periodic table, animals, evolution, rainbows, earthquakes, seasons, the sun, our solar system, and the universe, among others. Dawkins draws on facts from scientific evidence. So what is the problem with this book?

The trouble lies in its audience.

Dawkins’ name is synonymous with many things: scientist, biologist, public speaker, and atheist. His first non-fiction book, The Selfish Gene, was immensely popular upon publication in 1976, and his reputation among academics and intellectuals grew with each subsequent release. But it was not until the British-born scientist published The God Delusion in 2007 that his name became interchangeable with “controversial”.

Since then it seems that, in the eyes of many religious people, Dawkins’ personal beliefs (or more accurately, lack of personal beliefs) have eclipsed his long list of academic accomplishments. So what does this mean for The Magic of Reality?

Unlike Dawkins’s other books, The Magic of Reality took a much younger audience into account. With glossy illustrations and jargon-free language, Dawkins makes it no secret that he hopes to educate and inspire the minds of the next generation. In promotional interviews, he encourages parents to read the book with their children, filling in any “missing links” their impressionable offspring may come across.

Unfortunately, it seems that some parents—the same parents who only equate Dawkins’s name to The God Delusion—are the ones obsessed with finding “missing links” in Dawkins’ latest book.

Each chapter in The Magic of Reality begins with a brief introductory myth that has been used to explain certain phenomena in our universe, followed by Dawkins’ scientifically proven answers to each phenomenon. For example, in the chapter on earthquakes, Dawkins mentions, “some Siberian tribes believed that the Earth sat on a sledge, pulled by dogs and driven by a god called Tull. The poor dogs had fleas, and when they scratched, there was an earthquake.”

After a few more earthquake myths, Dawkins finally clears his throat: “We need to hear the remarkable story of plate tectonics.”

Dawkins’ blunt certainty appears to be a contributing factor to limiting readerships, especially in conservative families. Seeing a personal religious belief of the world under a heading labelled “myth” can naturally be disheartening. Many media outlets are also clinging onto Dawkins’ atheistic views when citing The Magic of Reality.

Despite some of the negative attention, the book is still selling well, and the book tour is bringing in large crowds. But it is doubtful that the majority of these readers are actually children. More likely, the audience consists mainly of adult atheists and Dawkins fans—people who have already made up their minds about the information in The Magic of Reality, and are simply purchasing the book to support Dawkins. This youngster market is undoubtedly made up of the sons and daughters of Dawkins’ fans.

Dawkins does not intend to convert religious children into hedonist monsters. The goal of The Magic of Reality, to my mind, is simple: to teach critical thinking to children.

Many people hear an explanation, but they don’t listen to the explanation. This is the basis of critical thinking. By introducing myths at the beginning of each chapter and then supplying the scientific explanations afterward, Dawkins is comparing the hearing with the listening—the myths with the evidence. He even states: “To claim a supernatural explanation of something is not to explain it at all and, even worse, to rule out any possibility of its ever being explained.”

Richard Dawkins’ name is synonymous with many things, but lately “atheist” and “controversial” are the only two that mean anything to the public. It’s a shame, because The Magic of Reality truly is a remarkable, poignant, and well-crafted book. And if anyone, theist or atheist, is in the market for an educational book for children, I’d recommend this one. After all, its author is still a scientist, ethologist, biologist, intellectual, and public speaker—and these fields are much more universal than personal philosophies.