Munirul-Haq Raza | News Editor

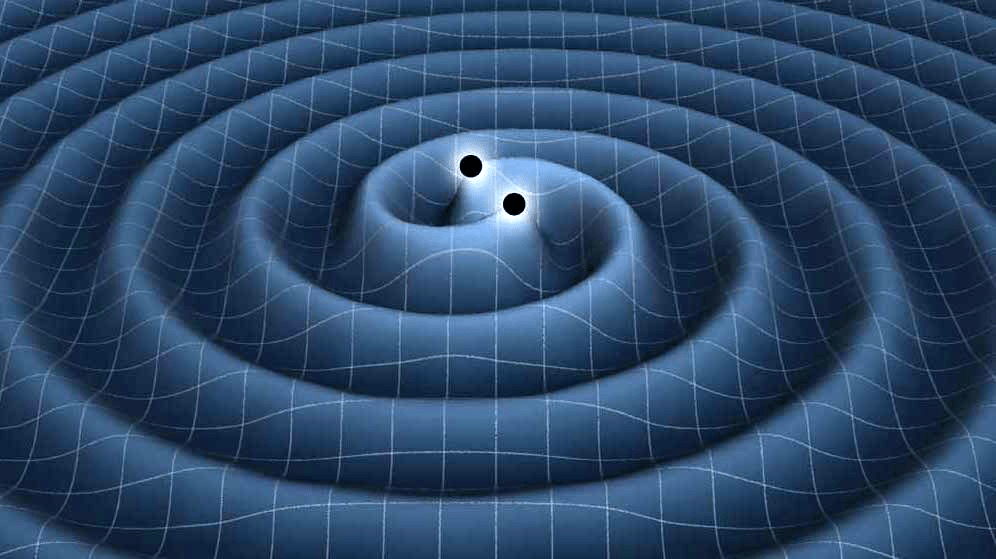

Featured image: The talk focused on the nature of gravitational waves and how they connect to fundamental physics at the most extreme energy scale. | Courtesy of NASA

On February 7, York’s Astronomy Club (ACYU) hosted a talk by Carl-Johan Haster, a postdoctoral fellow at The Canadian Institute for Theoretical Astrophysics at the University of Toronto.

The talk focused on the nature of gravitational waves and how they connect to fundamental physics at the most extreme energy scale.

Haster hopes that “we’ll learn about the state of matter under extreme conditions [things being torn apart by black holes will ‘by construction’ experience the strongest gravity there is]. Eventually, we’ll find the point where general relativity breaks down—which needs to happen.”

He adds this is understood “since the current formulation of general relativity still doesn’t work together with quantum mechanics, and at some point the sources we’re observing will have to account for both theories.”

Further, the speaker explored what gravitational waves can determine about the darkest and brightest events in the universe.

He says that gravitational waves can teach us about the “formation and evolution of individual stars, which spread across the universe from many differing environments.

“We can—most likely in the far future—learn about the Big Bang to a greater detail than any electromagnetic observations can provide; gravitational waves will be able to penetrate the early universe much further back than electromagnetic can.”

Gravitational waves were first detected by The Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory. Matthew C. Johnson, an assistant professor of Physics and Astronomy at York, explains that “gravitational waves are moving disturbances in space time itself,” describing the original discovery as “the first true test of full general relativity,” and “far more rigorous” than previous tests of the theory.

Johnson says that compared to previous tests like the Hulse–Taylor pulsar, the bending of light around mass, time dilation caused by proximity to a massive object, and other tests, “you are not ever probing a gravitational field that is, in a sense, very strong.”

He adds: “In some theories of cosmology, you predict that there are gravitational waves produced very early in the universe,” and that those gravitational waves might be detected in an indirect way, based on how they interacted with light produced in the early universe.

When asked if gravitational waves travel at the speed of light, Haster says: “In August 2017, we observed both gravitational wave signals and a gamma ray signal from the same physical source. Based on this timing difference—approximately two seconds—and knowing the distance between the source and the Earth, we can measure the relative speed of gravity and light. The prediction from Einstein’s Theory of General Relativity is that both signals are to travel at the same speed.” He adds that gravitational waves traveling at the speed of light is measured to an accuracy of one part in quadrillion (or 1,000 trillion).

Haster adds with his hope for future discoveries from gravitational waves: “So far, we’ve only seen gravitational waves from sources we understand, and know what they are. Every time humanity has gained a new way of observing the universe, we’ve seen signals from sources we couldn’t have predicted (gamma-ray bursts, radio pulsars, x-ray binaries, and many others), so eventually, we should see something completely new and unexplained.”